Alibaba's Governance by Politburo: Corporate Governance and Value

In my last post on Alibaba, I valued the company at about $162 billion but also argued that investors considering investing in the company might hold back because of corporate governance concerns. I will start by making the case (and it is an easy one) that Alibaba is more corporate dictatorship than corporate democracy, but I would then like to use the company as a vehicle to talk about what constitutes good corporate governance and how best to incorporate its presence or absence into value.

The Alibaba Corporate Governance Model

In theory, the stockholders in a publicly traded company are its owners and get to determine who runs the company and how it is run. In practice, we know that this is more myth than reality and that a variety of constraints, both internally and externally imposed, exist on stockholder power. Even in the most idyllic corporate democracies, incumbent managers start off with an advantage over stockholders in the power game, though activists can sometimes even the playing field. With a company like Alibaba, stockholder don't even have the fig leaves of choice that they do with most other publicly traded companies and there are three reasons why:

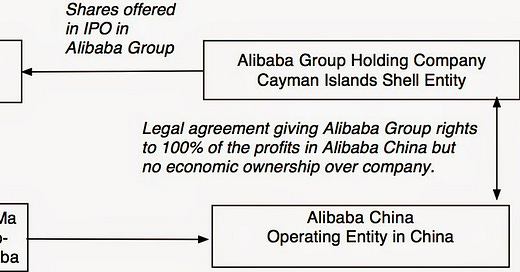

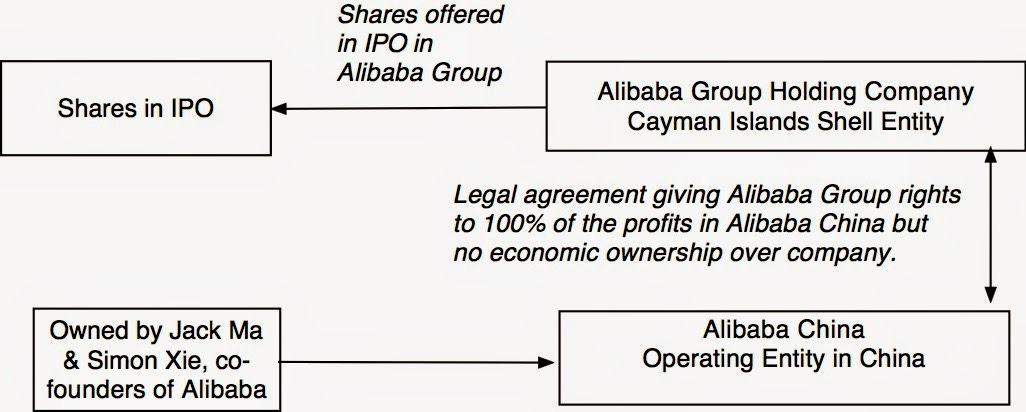

Legal Structure: The corporate governance problem with Alibaba starts with its legal structure. As I have noted in my prior posts, if you buy shares in Alibaba, you are not getting a piece of Alibaba, the Chinese online merchandising profit-machine, but a portion of Alibaba, the Cayman-Islands shell entity that has a contractual arrangement to operate its Chinese counterpart. While the Chinese government has granted legal standing to that contractual agreement, at least for the moment, it reserves the right to change it's mind and if it does, Alibaba's shareholders will be left with just the shell.

Operating Structure for Alibaba

Management Powers: While the board of directors in publicly traded companies often fail in their obligation to protect the interests of stockholders, stockholders at least get to elect board members and have a say (nominal thought it may be) in the management of the company. With its partnership set-up, Alibaba has stripped even this minimal power away from stockholders, and the board will be named by a group of partners, which includes Jack Ma and his hand-picked partners. This is decision by corporate politburo, not through corporate democracy, but to give the Hong Kong Stock Exchange credit, they refused to allow Alibaba a listing with this set-up, but the NASDAQ NYSE seemed to have no qualms. In fact, given the NASDAQ’s NYSE's track record of going after large market cap listings at any cost, is there is any entity (Atilla the Hun? The Evil Empire?), with sufficient market capitalization, that the NASDAQ NYSE would refuse to list? (In my initial version of this post, I had wrongly accused the NASDAQ for this listing sin and I apologize, since I am sure that the NASDAQ would never have been this craven).

Country setting: China has been the growth story of the decade and there is much to admire in the country’s single minded focus at making itself a first world economy. However, it is not a market economy in any sense of the word and I do not believe that the management at a Chinese company, let alone one as large and high-profile as Alibaba, can survive, if it upsets the Beijing power structure. Thus, it not only does not surprise me to read stories like this one about ties with politics but it brings home the realization that what stockholders want for this company is irrelevant, if their wants are not consistent with what the Chinese government would like to see happen.

In effect, you have a corporate non-governance trifecta, a publicly traded entity with questionable legal standing, run by a strong willed CEO who can write his own rules, in a country that does not put much weight on ownership rights. To give Alibaba credit, they do not hide the fact that this is a company where stockholders are powerless, as evidenced by this section from the prospectus (Pages 57-60), where they are clear that they are not required to maintain the illusion of board independence and accountability that most public corporations are required to.

What is corporate governance?

Now that we have established that stockholders in Alibaba have no power, it is time to ask a broader question about what exactly constitutes good corporate governance. In the last three decades, academic research and shareholder services have followed a standard path to measuring corporate governance by looking at the corporate charter and the composition of the board of directors. Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), which provides perhaps the most widely used measure of corporate governance, builds its quick score around four pillars: an audit pillar (looking at whether the company makes its financial filings in time), a board pillar (director composition, compensation and shareholder approval rates), a shareholder rights pillar (hostile takeover restrictions, ease of dilution) and a compensation pillar (whether it is aligned with performance, how much say stockholders have in setting it and how well it is disclosed). Through no fault of ISS, companies have learned the system and play it well, meeting the checklist criteria for good corporate governance while rendering the concept toothless.

While I understand the need to use objective measures to arrive at corporate governance scores, my definition of corporate governance is both broader and more difficult to measure. It reflects the power of stockholders to change the management of a company, if they feel the urge to do so. In that sense, it is very similar to the power that voters have in a democracy, to change their government. Note that the right to change management (or a government) may not always be exercised, because stockholders (voters) are lazy and abstain, or be exercised wisely, insofar as stockholders (voters) may leave bad managers (governments) in place or replace good managers (governments). The key is that with they have the power to create change, if they choose to.

Corporate governance and corporate performance

Proponents of stronger corporate governance argue that it critical to corporate performance, but the evidence of the link between the two is not very strong. There are badly run companies with impeccable corporate governance in place and superbly performing businesses where there is absolutely no restraint on corporate managers. Google and Facebook are corporate fiefdoms, where founder/CEOs have unchallenged power to do almost anything that they want, but they are also companies that have delivered immense profits and value to their stockholders.

It is true that generalizing on the basis of anecdotal evidence is dangerous, but studies that look at the overall relationship between measures of strong corporate governance and value deliver the same fuzzy message that good corporate governance does not always translate into higher value or better performance. One of the most widely quoted studies in support of strong corporate governance is this one, which finds that companies with stronger stockholder rights have higher profits and trade at higher multiples than companies with weak governance. Other studies, though, note that the the correlation between corporate governance measures and stock performance is weak and that there is some evidence that subsets of firms with weak corporate governance deliver superior performance.

As in the previous section, you can use an analogy from political governance to examine the link of governance with performance. Is a country better off run by a benevolent (and intelligent) ruler-for-life or by a sometimes chaotic, often messy democracy? As someone whose instincts tend towards the latter, I would love to tell you that the answer is obvious, but I have had my moments of frustration with self-serving, short-term legislation and populist politicians, when I have dreamed about the former.

The Value of Corporate GovernanceAt the start of each of my valuation classes/sessions, I start with what I call the It Proposition and here is how it goes, “If it does not affect the cash flows or the risk in an investment, it cannot affect value”. If you are wondering what “it” is, “it” can be any of those words that are used to justify adjusting value with premiums (control, synergy, brand name) or discounts (illiquidity). Since it would be hypocritical of me to abandon this proposition in the context of corporate governance, I would argue that any corporate governance effect on value has to show up in either the cash flows or the risk.

Valuing Corporate Governance: The Static Framework

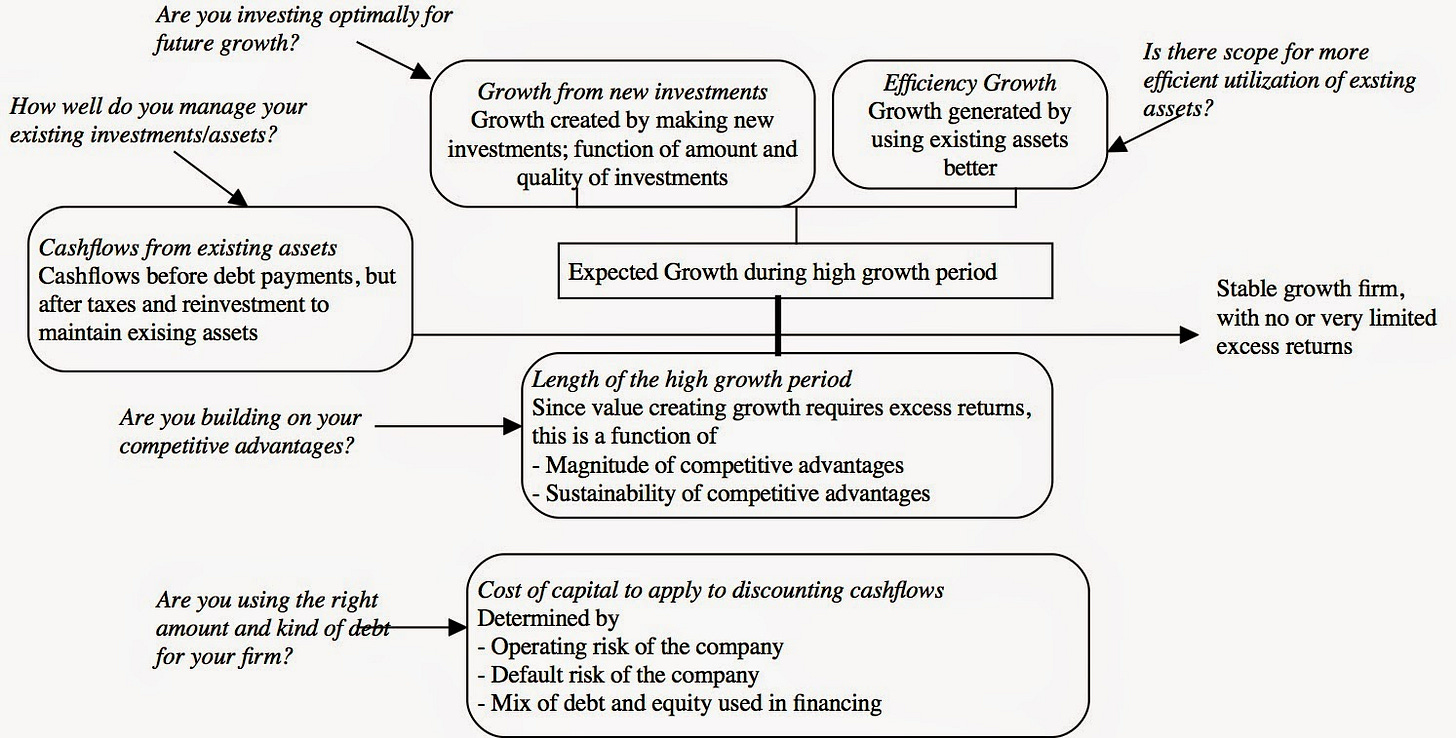

To consider how best to incorporate good or bad corporate governance into the value of a company, consider the determinants of value. We make judgments about how well a company is managing its existing assets, how much value there will be in future growth and the risk in the business to arrive at an estimate in value.

These judgments, though, are based upon assumptions about who is running the company (the management) and what these incumbent managers do well or badly. Thus, if you are valuing a company where managers have had a history of delivering high growth efficiently but are conservative when it comes to the use of debt, you may assume continued high quality growth accompanied by predominantly equity funding in valuing the company. In contrast, if you are valuing a company that borrows too much and consistently over pays on acquisitions, you may assume that those destructive tendencies will continue in valuing the company. Let’s term these the status quo values. Now, consider revaluing these companies with a new management in place without the blind spots of the status quo managers and reassess investment, financing and dividend policies. This will require you to take a fresh look at the key inputs into value, and with the changes that you make in how the company is run, you can revalue the company. Let’s term this value the optimal value.

By definition, the optimal value cannot be lower than the status quo value, but it can be equal to it (in the unlikely event that your company is perfectly run by the existing management) and will generally be greater. Now that you have the status quo value and the optimal value of a publicly traded company, you can write the expected value of the company as a probability weighted average of the two numbers:

Expected value of company = Status Quo Value (Probability of Existing Management staying in place) + Optimal Value (1 – Probability of Existing Management staying in place)

Note that the probability attached to the optimal value can be construed as the probability of management change and it gives us a platform for assessing the value of corporate governance. If corporate governance is weak or non-existent, the probability of changing management decreases and the expected value of a company will converge on the status quo value. That may not result in significant value loss, if you have a well managed company, but the discount for bad corporate governance can be significant for a poorly managed company.

Valuing Corporate Governance: The Dynamic Framework

The static approach to valuing corporate governance tends to work better for mature companies that are set in their ways. It does not work as well for younger companies that are run by strong willed CEOs, but are also perceived as being run well (at least for the moment). In these companies, the status quo and the optimal values may converge, leading to the conclusion that corporate governance does not have an impact on value. Thus, if you were valuing Google or Facebook, companies with excellent track records and imperial CEOs, you may conclude that there is little consequence to having poor corporate governance.

Taking a longer-term perspective, and borrowing again from the political governance framework, the advocates for strong corporate governance would argue that there is a cost to bad corporate governance even at companies that are well managed today, since you are buying a share of these companies in perpetuity. That cost will show up in the future, when managers make wrong choices (and even the best ones do) or take value destructive paths. Since they are not accountable to stockholders and boards tend to be rubber stamps, there is no mechanism for bringing them back on track and the costs in the long term can be immense to stockholders. Even with the longer term perspective, though, there are others who argue that the restraints put on top management in a strong corporate governance system will result in slower and sub-optimal decisions, perhaps costing investors value in future periods.

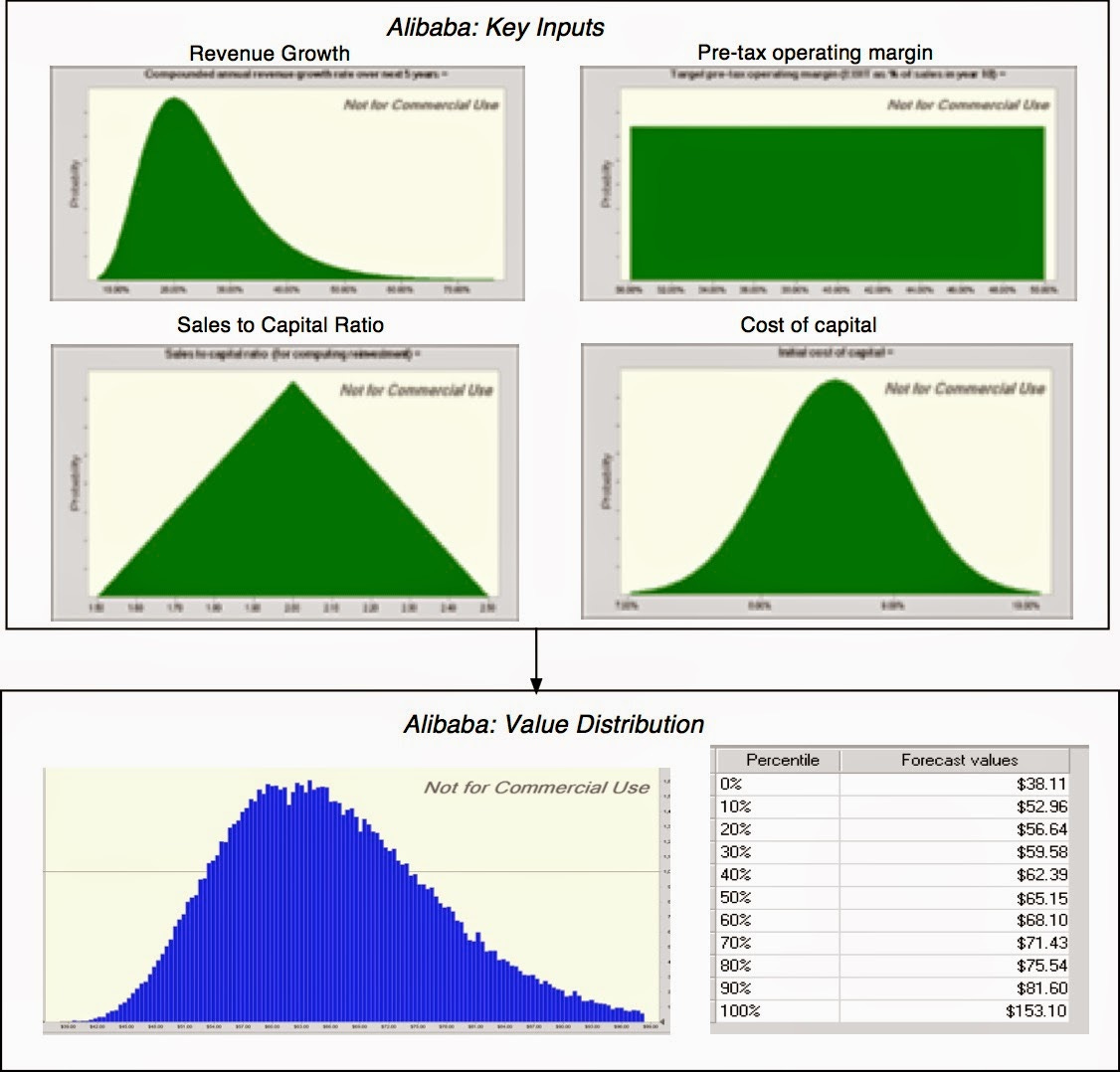

In valuation, the question of how best to capture this long term risk is a difficult one to answer. It is almost impossible to do in conventional valuation, where you make you base your value on your expected values for growth, risk and cash flows. It is possible, however, to get a sense of how much corporate governance matters, if you are willing to estimate a distribution for value, allowing for both good and bad decisions/outcomes. Returning to my Alibaba valuation, I reframed the inputs on revenue growth, operating margin, reinvestment and risk (cost of capital) as distributions (rather than point estimates) and estimated a distribution of value for the equity per share in the company:

Notice that while the expected value ($66.45/share & $162.9 billion in equity) and median value ($65.15/share & $159.7 billion in equity) are close to my base case valuation ($65.98/share & $161.7 billion in equity), there are outcomes that diverge widely from these numbers. Based on my assumptions, Alibaba could be worth as little as $38.11/share ($93.7 billion), if revenue growth drops, margins sag and risk rises, or as much as $153.10/share ($ 374.4 billion ). While this is going to be true for any firm with uncertainty about the future, the distribution of value allows us to get perspective on the contrasting points of view about strong management.

The Benevolent Ruler school: Investors in this school see an upside to unrestrained managers, arguing that there will be opportunities that will open up for the company to increase its value that require the quick, decisive and consistent actions that a strong, informed CEO can make without having to worry about or being slowed down by stockholder reactions or board approval. In effect, investors in this school may actually add a premium to discounted cash flow value to reflect the CEO's power, because they believe that a stronger CEO makes it more likely that Alibaba's value will converge on a higher number.

The Corporate Democracy school: Investors in this school believe that CEOs with absolute power will inevitably make mistakes, and lacking accountability to shareholders and an active board of directors, will continue down value-destructive paths. Not surprisingly, these investors will reduce their DCF value to reflect this probability.

The determinants of the premium attached by the first school and the discount tacked on by the second school are surprisingly similar. They will both increase as the uncertainty in the value of the business increases, since they have the characteristics of an option: a call option that adds value for the benevolent ruler school and a put option that reduces value with the corporate democracy school. They will also increase with your time horizon as an investor, with longer time horizons associated with higher values for both the premium and discount. Thus, if you are investor with a ten-year time horizon, you care a lot more about the good and bad qualities of top management than if have a six-month time horizon. That, in turn, may explain why so few portfolio managers and investors seem to be even looking at the corporate governance question with Alibaba with any concern.

The Bottom Line

As a long term investor, I am torn. While I think that Alibaba's current management team has done an superb job in building up the company, my instincts as an investor and my memories of well-managed companies that have mutated into badly run ones (with the same CEO in place) make me hold back. To be honest, I don't like being asked for my money (as an investor) and then being told that I have no say in how its run. With Alibaba, the decision is easier for me, at least for the moment, because the company is, at best, fairly priced at its offering price. It will be a decision, though, that I will have to revisit, if the price drops and the value does not. In effect, I will have to decide the discount on value at which I am okay with being in Jack Ma's outhouse.

Attachments

Alibaba: A China Story with a Profitable Ending (My May 8th post on Alibaba)

Alibaba's Coming out Party: Fairly Valued but is it fairly priced? (My September 8th post on Alibaba)

The value of control (My paper on status quo and optimal values)

My simulation assumptions for Alibaba (You will need Crystal Ball or some variant to be able to run the simulation yourself)