Back to Apple: Thoughts on value, price and the confidence gap

I know that you are probably sick and tired of reading about Apple, and I am getting close to that point too, but this post is really more about investing than it is about Apple. In my post on Apple on January 27, I also posted "my" distribution of value for Apple, concluding that there was a 90% chance that Apple was under valued. One of the responses I got was interesting and it questioned the courage of my convictions by asking why, if I believed that there was a 90% chance that the stock was under valued, I would not "bet the house" (I put a 10% cap on Apple in my portfolio). That, of course, gives me a platform to return to a theme that I have harped on for much of the last year: that valuation and pricing are two very different processes and that many analysts/investors often being confident about one does not imply confidence about the other.

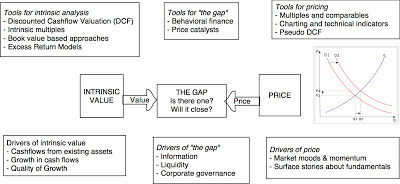

To set the table for the comparison, let me start with my assessment of the differences between the valuation and pricing processes.

The value of a business is determined by the magnitude of its cash flows, the risk/uncertainty of these cash flows and the expected level & efficiency of the growth that the business will deliver. While discounted cash flow valuation may be one way of estimating this value, there are other intrinsic value approaches that also try to do the same thing: estimate the intrinsic or fair value of a business.

The price of a publicly traded asset (stock) is set by demand and supply, and while the value of the business may be one input into the process, it is one of many forces and it may not even be the dominant force. The push and pull of the market (momentums, fads and other pricing forces) and liquidity (or the lack thereof) can cause prices to have a dynamic entirely their own, which can lead to the market price being different from value.

Last year, in the aftermath of the Facebook IPO, I posted on the difference between pricing and valuation and my view that much of what passed for valuation in Facebook (in the IPO pricing by the investment banks and by investors in the aftermath) was really pricing. In fact, I think that this picture illustrates my point:

So, let us assume that you value a company (using whatever your favored valuation tool) is and come to the conclusion that there is a gap between the value and the price. Before you act on this value, you have to answer three questions:

How confident are you about the magnitude of the gap? Since you know the market price, this is entirely a question about the confidence you have in your valuation.

How confident are you that the gap will close? This, unfortunately, is generally not in your control and will be driven by the pricing process.

What are the catalysts that can cause the gap to close? If the gap is to close, the price has to move towards your value and you need "something" to get it started.

In sum, whether you invest will depend upon the answers to all three questions. You could, therefore, find a big gap between value and price, feel confident about your estimate of value and not invest in the stock, if you don't feel comfortable with the forces that are driving the market price or hopeful about catalysts in the near future. Let me apply this structure to Apple to reconcile my assessment that there is a 90% chance that Apple is under valued at $440/share and my decision to cap my holding of Apple at 10% of my portfolio.

The Magnitude of the Gap

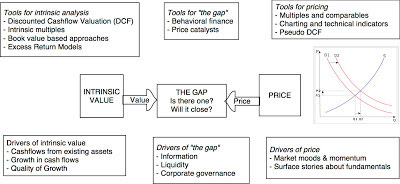

I started with a discounted cash flow valuation of Apple at the end of 2012, which yielded $608/share. With the stock trading at $440, that gives me an estimated gap of $168, impressive but meaningless without a measure of confidence about the magnitude of the gap. To arrive at this confidence measure, I used Crystal Ball (an add-on to Excel that allows you to do Monte Carlo simulations) and revalued Apple, with distributions, rather than single values, for three key inputs: revenue growth rate in the near term, target operating margin and a cost of capital. The results of 100,000 simulations (that is the default in Crystal Ball) yielded the distribution for values for Apple:

APPLE SIMULATION RESULTS: END OF 2012

All that I did to arrive at the 90% estimate that Apple was under valued was count the number of simulations that delivered values less than $440; in reality, it was closer to 94% but I rounded down to 90%. Note that to end up at values less than $440, the distributions for the key variables all had to be close to the "bad" ends of their distributions. Thus, for Apple to be worth only $440 (or less), you would need negative or close to zero revenue growth, pre-tax operating margins of 25% (current margin is closer to 35%, down from 40% plus a year ago) and the cost of capital would have to be at 15% (the 97th percentile of US stocks).

The Closing of the Gap

Now, comes the trickier question. Will the gap close and if so, when? There are three factors to consider in making this judgment:

(a) Information: Are you using information in your valuation that the market does not have yet? I know that this would be dangerously close to insider trading in the US, but it is possible that in some markets, you have to access to proprietary information. The gap will close when then information is revealed. With Apple, I used the company's filing with the SEC, and there is no private information in the valuation. I have exactly the same information as everyone else in the market does.

(b) Liquidity: Are there market trading restriction or liquidity barriers that are preventing the price from adjusting to value? If you have a lightly traded stock, with minimal float, it is possible that the price may stay different from value, until trading picks up. If the stock is over valued (price > value), there may be restrictions on short selling that prevent the price from adjusting to value. With Apple, given its market cap and liquidity, I don't see this as a a problem.

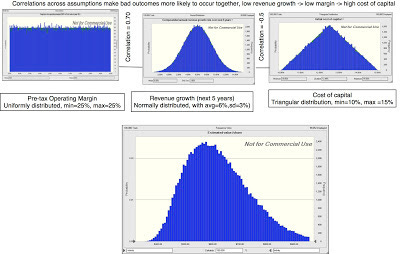

(c) Behavioral forces: What are the pricing forces in the market and which direction are they pushing the gap? As I noted at the start, prices are subject to the push and pull of momentum, to institutional investors flocking into a stock and then abandoning it and to equity research analysts blowing hot and cold about its next earnings report. With Apple, these forces, for the last year and a half, have been powerful and unpredictable, pushing the price up to $705 a few months ago and down to $440 now. Part of the unpredictability comes from the mix of growth, value and momentum investors who drive the price and part of it comes from the rumor/news ecosystem that the market has developed to fill in the news vacuum created by Apple's secrecy about its future plans. As a consequence, the price/value gap could stay where it is or even get larger in the near term, but the odds of the gap closing do improve as you extend your time horizon. For instance, here are my very rough estimates (based on what I know about momentum and price movements in stocks over short and long periods) of what I see happening to the gap, as a function of time horizon:

Over the next month, there is a higher chance that the gap will increase rather than decrease, but as the horizon extends, the likelihood of the gap increasing drops. But here is the bad news for intrinsic value investors. Even with a 10 year time horizon, and assuming that you are right about value, there is still a non-trivial chance that the gap will get bigger. Hence, there is good basis for the old Wall Street adage: that the market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.

The Catalyst

If there is a gap between price and value and that pricing gap persist, it is no surprise that investors start looking for catalysts that can cause the gap to close. Not surprisingly, there is no easy model to follow, but here are some choices:

a. Be your own change agent: As investors, it would be nice if we could tilt the game in our favor by having some influence over the gap. While you and I may not be able to do much to alter market dynamics, this is a place where activist investors with enough money and access to megaphones can make their presence felt. And the good news for the rest of us is that we can sometimes piggyback on their success. As Apple investors watch Nelson Peltz tussle with Danone and Bill Ackman take on Herbalife, they may find fresh hope in David Einhorn's frontal run at Apple.

b. A company act/decision: While publicly traded companies often play the role of helpless victims to the pricing process, they feed the momentum beast when it works in their favor. In my last post, I noted some actions that Apple can take to cause prices to move towards value including being more open about their long term plans, returning more cash to stockholders and finding new markets to disrupt.

c. A market shift: It remains one the great mysteries of markets. Momentum has a life of its own and it does shift, often in response to small events. While I am not a tape watcher, I believe than trading volume shifts, historically, have been better predictors of momentum changes than watching pricing charts. So, if your technical analysis skills have not rusted, get busy!

Speaking of Einhorn, the news stories today are about his suggestion that Apple issue preferred shares to its common stockholders with a 4% dividend. I am afraid that this post has already gone on too long for me to comment at length, but here is what I believe. Issuing preferred shares will have no effect on value (so, forget about unlocking value...) but the best case scenario is that it will be a price catalyst, by convincing (some) stockholders of the company's commitment to return cash to investors in the future. Cryptic, I know.. but I will have a separate post on it tomorrow.

The Bottom Line

Summing up, my high confidence that there is a big gap between value and price (that Apple is under valued) is tempered by my low confidence, at least in the near term, that the gap will close substantially and that there will be a dramatic game changer (catalyst) in the next few months. While I have a long time horizon, it is not entirely within my control (since I have no idea what financial emergencies may lie in my future), and hence my cap on my Apple investment. In fact, it was the fear of the havoc that these forces could wreak that led me to sell Apple in April 2012, when the stock was trading at $600+ (at my estimated value of $700, there was a 60% chance that it was under valued).