Chill, dude (Part II): Debt Default Drama Queens

When I took my first finance class, I was taught that the government bond rate in the currency in question is the risk free rate. Implicit in that teaching was the assumption, misplaced even then, that governments do not default on their local currency borrowings, since they control the printing presses. When confronted with evidence of government defaults in the local currency in prior decades, the defense offered was that these defaults occurred in tumultuous emerging markets but would never happen in developed markets. I took that teaching to heart and for almost three decades used the US Treasury bond unquestioningly as the risk free rate in US dollars. With the government default looming tomorrow, you would think that this would be a moment of reckoning for me, but my faith in governments being default free was lost a while back, in September 2008. For those who do remember that crisis (and it is amazing how quickly we forget), there were two events that month that changed my perceptions of government default. The first occurred on September 17, 2008, where money market funds (supposedly the last haven for truly risk averse investors) broke the buck, essentially reporting that they had lost principal even though they had invested in supposedly risk free, liquid securities. The second happened a week later, when the nominal interest rate on a US treasury bill dropped below zero, an almost unexplainable phenomenon, if you believe that the US government has no default risk. After all, why would investors pay more than a thousand dollars today for a T.Bill for the right to receive a thousand dollars in the future, unless they perceive a chance that they will not be paid?

That last question is the key to understanding default risk. It is not a zero-one proposition, where it shows up only after you have defaulted. If an entity is truly default free, the question of whether there is default risk will never come up, and if it does come up, that entity is not default free. Put in specific terms, I believe that markets have perceived and built in some default risk in the US Treasury since 2008, though it is perhaps small enough to ignore. The issue was crystallized two summers ago, when S&P announced its ratings downgrade for the US, to screams of protest from politicians in DC. At the time, I posted my reaction to the downgrade and advised investors to take it down a notch and that while the downgrade was definitely not good news for any one, it was not the end of the world that it was made out to be.

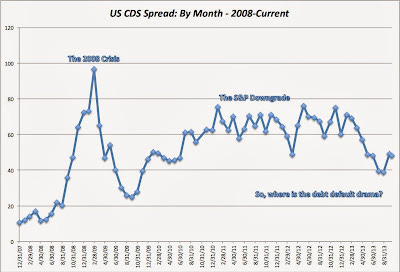

Market Assessments of US default riskTo back up my point about how default risk is not a zero one proposition to markets and investors, I will start with a graph of credit default swap spreads for the US on a monthly basis from January 2008 through today. While I have posted about the limitations of the CDS market, it provides a barometer of market views on sovereign default risk that are much more timely than sovereign ratings.

Looking at the chart, it is clear that the crisis is 2008 changed market perceptions of default risk in the United States. The US CDS spread increased from 0.105% in January 2008 to 0.73% in January 2009. While that number dropped back for a while, it started climbing again in late 2010 and the S&P downgrade in August 2011 had little impact on the spread, suggesting that as always, ratings agencies follow markets, rather than lead them. Updating the numbers through this year, the US CDS spread has dropped over the course of the year and the debt default drama has had little impact on that number, suggesting again that while the recent events in Washington may have increased investor concern about default risk, the effect is not as large or as dramatic as it has been made out to be.

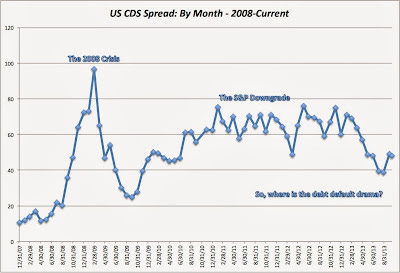

If you are concerned that the month to month graph might not be indicating day to day volatility in the market, this graph should set that fear to rest:

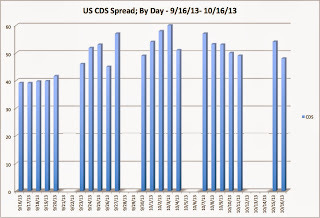

Some analysts have pointed at the increase in the T.Bill rate as evidence of market concern about default and there is some basis for that.

The one-month T. Bill rate has climbed from zero in mid-September to 0.35% yesterday. However, note that the US T.Bond rate actually declined over the same period, again indicative that if there is a heightened sense of worry about default with the US Treasury, it is accompanied by a sense that the default will not last for long and will affect short term obligations by more.

Valuation Implications

What are the implications of heightened default risk in government bonds for risky assets? In the immediate aftermath of the 2008 crisis, I worked on a series of what I call my "nightmare" papers, where I took fundamental assumptions we make about markets and examined how corporate finance and valuation practice would have to change, if those assumptions were not true. The very first of those articles was titled, "Into the Abyss: What if nothing is risk free?" and it looked at the feedback effects of government default into valuation inputs. You can download the paper by clicking here, but I can summarize the effects on equity value into key macro inputs that affect the value of every company:

1. Risk free rate: How will a default or a heightened expectation of default by the US government affect the risk free rate in US dollars? It is tough to tell, but my guess is that the risk free rate in US dollars will decline. That may surprise you, but that may be because you are still equating the US treasury bond rate with the risk free rate in US dollars. Once government default become a clear and present danger, that equivalence no longer holds and the risk free rate in US dollars will have to be computed by subtracting out the default spread for the US from the US treasury bond rate. Thus, just as a what if, assume that there is default and the US T.Bond rate jumps from 2.60% today to 2.75% tomorrow and that your assessment of the default spread for the US (either from a newly assigned lower sovereign rating or the CDS market tomorrow) is 0.25%.

Risk free rate in US dollars = 2.75% - 0.25% = 2.50%

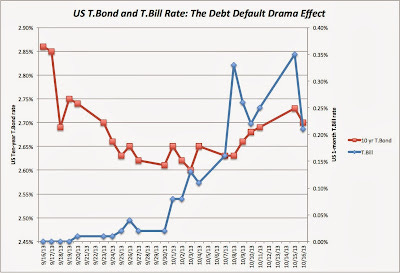

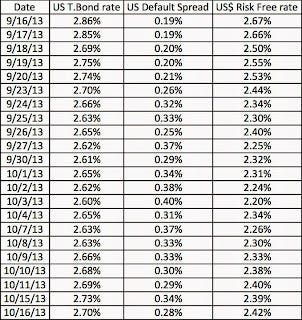

Why do I expect the risk free rate in US dollars to drop? A pure risk free rate is a composite of expected inflation and expected real interest rate, and as I have argued before, reflects expectations of nominal growth in the economy. A default by the US treasury will affect both numbers negatively, since it may tip the economy back into a recession and bring lower inflation with it. In fact, looking back at the daily T.Bond rates and CDS rates over the last month, I tried to break down the T.Bond rate each day into a risk free US $ rate and an estimated default spread. To estimate the latter, I compared the CDS spread each day to the CDS spread of 0.20% on August 31, 2008.

If you go along with my estimates, the US $ risk free rate has dropped from 2.67% to 2.42% over the last 30 days, while the default spread has widened from 0.19% to 0.28%.

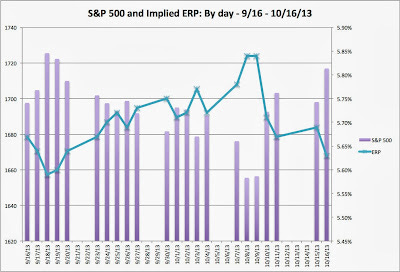

2. Equity Risk Premiums and Corporate Default Spreads: Lest you start celebrating the lower risk free rate as good for value, let me bring the other piece of the required return into play. If the default risk in the US is reevaluated upwards, it is also very likely that investors will start demanding higher risk premiums for investing in risky assets (stocks, corporate bonds, real estate). In fact, I think that the absence of a truly risk free alternative makes all risky investments even riskier to investors and that will show up as higher equity risk premiums. The same argument can be applied to the corporate bond market, where default spreads will increase for corporate bonds in every ratings class, as sovereign default risk climbs. To get a measure of how equity risk premiums have behaved over the last month, I can provide my daily estimates of the implied ERP from September 16 to October 16 for the S&P 500.

Note that I have computed the implied ERP over my estimated US$ risk free rate (and not over the US T. Bond rate). You can download the spreadsheet and make the estimates yourself. The net effect on equity will therefore depend upon whether equity risk premiums (ERP will increase by more or less than the risk free rate decreases. If default occurs, the ERP will increase by more than the risk free rate drops, which will have a negative effect on the value of equity. However, that effect will not be uniform, with the negative impact being greater for riskier companies than for safer ones.

The End Game

By the time you read this post, I would not be surprised if Congress has stitched together a last minute compromise to postpone technical default to another day. In a sense, though, it is too late to put the genie back in the bottle and while it is easy to blame political dysfunction for this debt default drama, I think that it is reflective of a much larger macro economic shift. With globalization of both companies and markets, even the largest economies are no longer insulated from big crises and in conjunction with the loss of trust in institutions (governments, central banks) over the last few years, I think we have to face up to the reality that nothing is truly risk free any more. That is the bad news. The good news is that the mechanism for incorporating that shift into valuation and corporate finance exists, is already in use in many emerging market currencies and just has to be extended to developed markets.