Data Update 4: Country Risk and Currency Questions!

In my last post, I looked at the risk premiums in US markets, and you may have found that focus to be a little parochial, since as an investor, you could invest in Europe, Asia, Africa or Latin America, if you believed that you would receive a better risk-return trade off. For some investors, in countries with investment restrictions, the only investment options are domestic, and US investment options may not be within their reach. In this post, I will address country risk, and how it affects investment decisions not only on the part of individual investors but also of companies, and then look at the currency question, which is often mixed in with country risk, but has a very different set of fundamentals and consequences.

Country Risk

There should be little debate that investing or operating in some countries will expose you to more risk than in other countries, for a number of reasons, ranging from politics to economics to location. As globalization pushes investors and companies to look outside of their domestic markets, they find themselves drawn to some of the riskiest parts of the world because that is where their growth lies.

Drivers and Determinants

In a post in early August 2019, I laid out in detail the sources of country risk. Specifically, I listed and provided measures of four ingredients:

Life Cycle: As companies go through the life cycle, their risk profiles changes with risk dampening as they mature. Countries go through their own version of the life cycle, with developed and more mature markets having more settled risk profiles than emerging economies which are still growing, changing and generally more risky. High growth economies tend to also have higher volatility in growth than low growth economies.

Political Risk: A political structure that is unstable adds to economic risk, by making regulatory and tax law volatile, and adding unpredictable costs to businesses. While there are some investors and businesses that believe autocracies and dictatorships offer more stability than democracies, I would argue for nuance. I believe that autocracies do offer more temporal stability but they are also more exposed to more jarring, discontinuous change.

Legal Risk: Businesses and investments are heavily dependent on legal systems that enforce contracts and ownership rights. Countries with dysfunctional legal systems will create more risk for investors than countries where the legal systems works well and in a timely fashion.

Economic Structure: Some countries have more risk exposure simply because they are overly dependent on an industry or commodity for their prosperity, and an industry downturn or a commodity price drop can send their economies into a tailspin. Any businesses that operate in these countries are consequently exposed to this volatility.

The bottom line, if you consider all four of these risks, is that some countries are riskier than others, and it behooves us to factor this risk in, when investing in these countries, either directly as a business or indirectly as an investor in that business.

Measures

If you accept the proposition that some countries are riskier than others, the next step is measuring this country risk and there are three ways you can approach the task:

a. Country Risk Scores: There are services that measure country risk with scores, trying to capture exposure to all of the risks listed above. The scores are subjective judgments and are not quite comparable across services, because each service scales risk differently. The World Bank provides an array of governance indicators (from corruption to political stability) for 214 countries (https://databank.worldbank.org/source/worldwide-governance-indicators#) , whereas Political Risk Services (PRS) measures a composite risk score for each country, with low (high) scores corresponding to high (low) country risk.

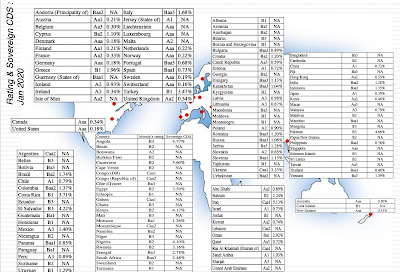

b. Default Risk: The most widely accessible measure of country risk markets in financial markets is country default risk, measured with a sovereign rating by Moody’s, S&P and other ratings agencies for about 140 countries and a market-based measure (Sovereign CDS) for about 72 countries. The picture below provides sovereign ratings and sovereign CDS spreads across the globe at the start of 2020:

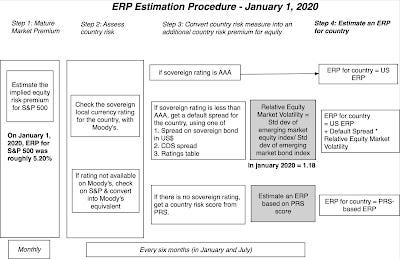

c. Equity Risk: While there are some who use the country default spreads as proxies for additional equity risk in countries, I scale up the default spread for the higher risk in equities, using the ratio of volatility in an emerging market equity index to an emerging market bond index to estimate the added risk premium for countries:

Note that the base premium for a mature equity market at the start of 2020 is set to the implied equity risk premium of 5.20% that we estimated for the S&P 500 at the start of 2020. The picture below shows equity risk premiums, by country, at the start of 2020:

Looking back at these equity risk premiums for countries going back to 1992, and comparing the country ERP at the start of 2020 to my estimates at the start of 2019, you see a significant drop off, reflecting a decline in sovereign default spreads of about 20-25% across default classes in 2019 and a drop in the equity risk, relative to bonds.

Company Risk Exposure to Country Risk

The conventional practice in valuation, which seems to be ascribe to all countries incorporated and listed in a country, the country risk premium for that country, is both sloppy and wrong. A company’s risk comes from where and how it operates its businesses, not where it is incorporated and traded. A German company that manufactures its products in Poland and sells them in China is German only in name and is exposed to Polish and Chinese country risk. One reason that I estimate the equity risk premiums for as many countries as I need them in both valuation and corporate finance, even if every company I analyze is a US company.

Valuing Companies

If you accept my proposition that to value a company, you have to incorporate the risk of where it does business into the analysis, the equity risk premium that you use for a company should reflect where it operates. The open question is whether it is better to measure operating risk exposure with where a company generates its revenues, where its production is located or a mix of the two. For companies like Coca Cola, where the production costs are a fraction of revenues and moveable, I think it makes sense to use revenues. Using the company’s 2018-19 revenue breakdown, for instance, the equity risk premium for the country is:

For companies where production costs are higher and facilities are less moveable, your weights for countries should at least partially based on production. At the limit, with natural resource companies, the operating exposure should be based upon where it produces those resources. Thus, Aramco’s equity risk premium should be entirely based on Saudi Arabia’s, since it extracts all its oil there, but Royal Dutch’s will reflect its more diverse production base:

Put simply, the exposure to country risk does not come from where a company is incorporated or where it is traded, but from its operations.

Analyzing Projects/Investments

If equity risk premiums are a critical ingredient for valuation, they are just as important in corporate finance, determining what hurdle rates multinationals should use, when considering projects in foreign markets. With L’Oreal, for instance, a project for expansion in Brazil should carry the equity risk premium for Brazil, whereas a project in India should carry the Indian equity risk premium. The notion of a corporate cost of capital that you use on every project is both absurd and dangerous, and becomes even more so when you are in multiple businesses.

The Currency Effect

When the discussion turns to country risk, it almost always veers off into currency risk, with many conflating the two, in their discussions. While there are conditions where the two are correlated and draw from the same fundamentals, it is good to keep the two risks separate, since how you deal with them can also be very different.

Decoding Currencies: Interest Rates and Exchange Rates

When analyzing currencies, it is very easy to get distracted by experts with macro views, providing their forecasts with absolute certainty, and distractions galore, from governments keeping their currencies stronger or weaker and speculative trading. To get past this noise, I will draw on the intrinsic interest rate equation that I used in my last post to explain why interest rates in the United States have stayed low for the last decade,

Intrinsic Riskfree Rate = Inflation + Real GDP Growth

That identity can be used to both explain why interest rates vary across currencies as well as variation in exchange rates over time.

Risk free Rates

If you accept the proposition that the interest rate in a currency is the sum of the expected inflation in that currency and a real interest that stands in for real growth, it follows that risk free rates will vary across currencies. Getting those currency-specific risk rates can range from trivial (looking up a government bond rate) to difficult (where the government bond rate provides a starting point, but needs cleaning up) to complex (where you have to construct a risk free rate out of what seems like thin air).

1. Government Bond Rates

There are a few dozen governments that issue ten-year bonds in their local currencies, and the search for risk free rates starts there. To the extent that these government bonds are liquid and you perceive no default risk in the government, you can use the government bond rate as your risk free rate. It is that rationale that we use to justify using the Swiss Government’s Swiss Franc 10-year rate as the risk free rate in Swiss Francs and the Norwegian government’s ten-year Krone rate as the riskfree rate in Krone. It is still the rationale, though you are likely to start to get some pushback, in using the US treasury bond rate as the risk free rate in dollars and the German 10-year Euro as the risk free rate in Euros. The pushback will come from some who argue that the US treasury can choose to default and that the German government does not really control the printing of the Euro and could default as well. While I can defend the practice of using the government bond rate as the risk free rate in these scenarios, arguing that you can use the Nigerian government’s Naira bond rate or the Brazilian government’s Reai bond rate as risk free is much more difficult to do. In fact, these are government’s where ratings agencies perceive significant risk even in the local currency bonds and attach ratings that reflect that risk. Moody’s rates Brazil’s local currency bonds at Ba2 and India’s local currency bonds at Baa2. In my pursuit of a risk free rate in currencies like these (where there is no Aaa-rated entity issung a bond), I compute a risk free rate by netting out the default spread:

Riskfree Rate in currency = Government bond rate – Default Spread for sovereign local-currency rating

Using this approach on the Indian rupee and the Brazilian reai,

Riskfree Rate in Rupees on January 1, 2020 = Indian Government Rupee Bond rate on January 1, 2020 – Default spread based on Baa2 rating = 6.56% - 1.59% = 4.95%

Riskfree Rate in Brazilian $R = Brazilian Government $R Bond rate on January 1, 2020 – Default spread based on Ba2 rating = 6.77% - 2.51% = 4.26%

Extending this approach to all countries where a local currency government bond is available, we get the following risk free rates:

Download spreadsheet

Note that these estimates are only as good as the three data inputs that go into them. First, the government bond rates reported have to reflect a traded and liquid bond, clearly not an issue with the US treasury or German Euro bond, but a stretch for the Zambian kwacha bond. Second, the local currency rating is a good measure of the default risk, a challenge when ratings agencies are biased or late in adjusting. Third, the default spread, given the ratings class, is estimated without bias and reflects the market at the time of the assessment.

2. Synthetic Risk free Rates

If you have doubts about one or more of three assumptions needed to use the government-bond approach to getting to risk free rates, don’t fear, because there is an alternative that I will call my synthetic risk free rate. To use this approach, let’s start with a currency in which you feel comfortable estimating a risk free rate, say the US dollar. If the key driver of risk free rates is expected inflation, the risk free rate in any other currency can be estimated using the differential inflation between that currency and the US dollar. In the short cut, you add the differential inflation to the US T.Bond rate to get a risk free rate:

Local Currency Risk free rate = US T.Bond Rate + (Inflation rate in local currency - Inflation rate in US dollars)

In the full calculation, you incorporate the compounding effects of the differential inflation

This approach can be used in almost any setting to estimate a local currency risk free rate, including the following:

Currencies with no government bonds outstanding: There are more than 120 currencies, where there are no government bonds in the local currency; the country borrows from banks and the IMF, not from markets. Without a government bond rate, the approach described above becomes moot.

Currencies where the government bond rate is not trustworthy: There are currencies where there is a government bond, with a rate, but an absence of liquidity and/or the presence of institutions being forced to buy the bond by the government that may make the rates untrustworthy. I don't mean to cast aspersions, but I seriously doubt that the Zambian Kwacha bond, whose rate I specified in the last section, has a deep or wide market.

Pegged Currencies: There are some currencies that have been pegged to the US dollar, either for convenience (much of the Middle East) or stability (Ecuador). While analysts in these markets often use the US T.Bond rate as the risk free rate, there is a very real danger that what is pegged today may be unpegged in the future, especially when the fundamentals don't support the peg. Specifically, if the local inflation rate is much higher than the inflation rate in the US, it may be more prudent to use the synthetic risk free rate instead of the US T.Bond rate as the risk free rate.

The key inputs here are the expected inflation rate in the US dollar and the expected inflation rate in the local currency. The former can be obtained from market data, using the difference between the US T.Bond rate and the TIPs rate, but the latter is more difficult. While you can always use last year’s inflation rate, but that number is not only backward looking but subject to manipulation. I prefer the forecasts of inflation that you can get from the IMF, and I have used those to get expected risk free rates in other currencies, using the US T.Bond rate as my base risk free rate, and you can find them at this link.

Currency Choice

Having belabored the reasons for why riskfree rates vary across currencies, let’s talk about how to pick a currency to use in valuing a company. The key word is choice, since you can value any company in any currency, though it may be easiest to get financial information on the company, in a local currency. An Indian company can be valued in US dollars, Indian Rupees or Euros, or even in real terms, and if you are consistent about dealing with inflation in your valuation, the value should be the same in every currency. At first sight, that may sound odd, since the risk free rate in US dollars is much lower than the risk free rate in Indian rupees, but the answer lies in looking at all of the inputs into value, not just the discount rate. In fact, inflation affects all of your numbers:

With high inflation currencies, the damage wrought by the higher discount rates that they bring into the process are offset by the higher nominal growth you will have in your cash flows, and the effects will cancel out. With low inflation currencies, any benefits you get from the lower discount rates that come with them will be given back when you use the lower nominal growth rates that go with them. In practice, there is perhaps no other aspect of valuation where you are more likely to be see consistency errors than with currencies, and here are some scenarios:

Casual Dollarization: In casual dollarization, you start by estimating your costs of equity and capital in US dollars, partly because you do not want to or cannot estimate risk free rates in a local currency. You then convert your expected future cash flows in the local currency and convert them to dollars using the current exchange rate. That represents a fatal step, since the inflation differentials that cause risk free rates to be different will also cause exchange rates to change over time. Purchasing power parity may be a crude approximation of reality, but it is a reality that will eventually hold, and ignoring can lead to valuation errors that are huge.

Corporate hurdle rates: I have long argued against computing a corporate cost of capital and using it as a hurdle rate on investments and acquisitions, and that argument gets even stronger, when the investments or acquisitions are cross-border and in different currencies. If a European company takes its Euro cost of capital and uses it to value Hungarian, Polish or Russian companies, not correcting for either country risk or currency differentials, it will find a lot of “bargains”.

Mismatched Currency Frames of Reference: We all have frames of reference that are built into our thinking, based upon where we live and the currencies we deal with. Having lived in the US for 40 years and dealt with more US companies than companies in any other market, I tend to think in US dollar terms, when I think of reasonable, high or low growth rates. While that is understandable, I have to remember that when conversing with an Indian analyst in Mumbai, whose day-to-day dealings in rupees, the growth rates that he or she provides me for a company will be in rupees. Consequently, it behooves both of us to be explicit about currencies (my expected growth rate for Infosys, in US dollars, is 4.5% or my cost of capital, in Indian rupees, is 10%) when making statements, even though it is cumbersome.

One of the side costs of globalization is that you can no longer assume, especially if you are a US investor or analysts, that the conversations that you will be having will always be on your currency terms (presumably dollars). Understanding how currencies are measurement tools, not instruments of risk or asset classes, will make that transition easier.

Conclusion

In this post, I looked at two variables, country and currency, that are often conflated in valuation, perhaps because risky countries tend to have volatile currencies, and separated the discussion to examine the determinants of each, and why they should not be lumped together. I can invest in a company in a risky country, and I can choose to do the valuation in US dollars, but only if I recognize that the currency choice cannot make the country risk go away. In other words, a Russian or Brazilian company will stay risky, even if you value it in US dollars, and a company that gets all of its revenues in Northern Europe will stay safe, even if you value it in Russian Rubles.

YouTube Video

Data Links

Ratings and Sovereign CDS spreads, by country (January 2020)

Government Bond Rates and Riskfree Rates by Currency in January 2020

Synthetic Riskfree Rates in 2020 (with inflation rates by currency)

Data Update Posts

Data Update 2 for 2020: Retrospective on a Disruptive Decade

Data Update 4 for 2020: Country and Currency Effects