Data Update 7 for 2023: Dividends, Buybacks and Cash flows

Fact and Fiction

This is the last of my data update posts for 2023, and in this one, I will focus on dividends and buybacks, perhaps the most most misunderstood and misplayed element of corporate finance. To illustrate the heat that buybacks evoke, consider two stories in the last two weeks where they have been in the news. In the first, critics of Norfolk Southern, the corporation that operates the trains that were involved in a dreadful chemical accident in Ohio, pointed to buybacks that it had done as the proximate cause for brake failure and the damage. In the second, Warren Buffet used some heated language to describe those who opposed buybacks, calling them “economic illiterates” and “silver tongued demagogues “. Going back in time to last year’s inflation reduction act, buybacks were explicitly targeted for taxes, with the perspective that they were damaging US companies. I think that there are legitimate questions worth asking about buybacks, but I don’t think that neither the critics nor the defenders of buybacks seem to understand why their use has surged or their impact on shareholders, businesses and the economy.

Dividend Policy in Corporate Finance

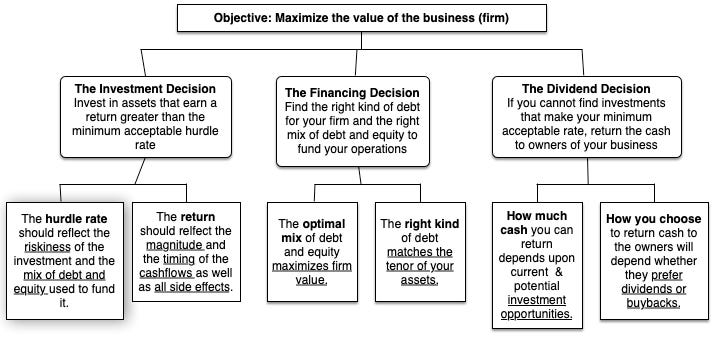

To understand where dividend policy fits in the larger context of running a business, consider the following big picture description of corporate finance, where every decision that a business makes is put into one of three buckets - investing, financing and dividends, with each one having an overriding principle governing decision-making within its contours.

In my fifth data update for 2023, I focused on the investment principle, which states that businesses should invest in projects/assets only if they expect to earn returns greater than their hurdle rates, and presented evidence that using the return on capital as a proxy for returns and costs of capital as a measure of hurdle rates, 70% of global companies fell short in 2022. In my sixth data update, I looked at the trade off that should determine how much companies borrow, where the tax benefits are weighed off against bankruptcy costs, but noted that firm often choose to borrow money for illusory reasons and because of me-tooism or inertia. The dividend principle, which is the focus of this post is built on a very simple principle, which is that if a company is unable to find investments that make returns that meet its hurdle rate thresholds, it should return cash back to the owners in that business. Viewed in that context, dividends as just as integral to a business, as the investing and financing decisions. Thus, the notion that a company that pays dividends is viewed as a failure strikes me as odd, since just farmers seed fields in order to harvest them, we start businesses because we plan to eventually collect cash flows from them.

Put in logical sequence, dividends should be the last step in the business sequence, since they represent residual cash flows. In that sequence, firms will make their investment decisions first, with financing decisions occurring concurrently or right after, and if there are any cash flows left over, those can be paid out to shareholders in dividends or buybacks, or held as cash to create buffers against shocks or for investments in future years:

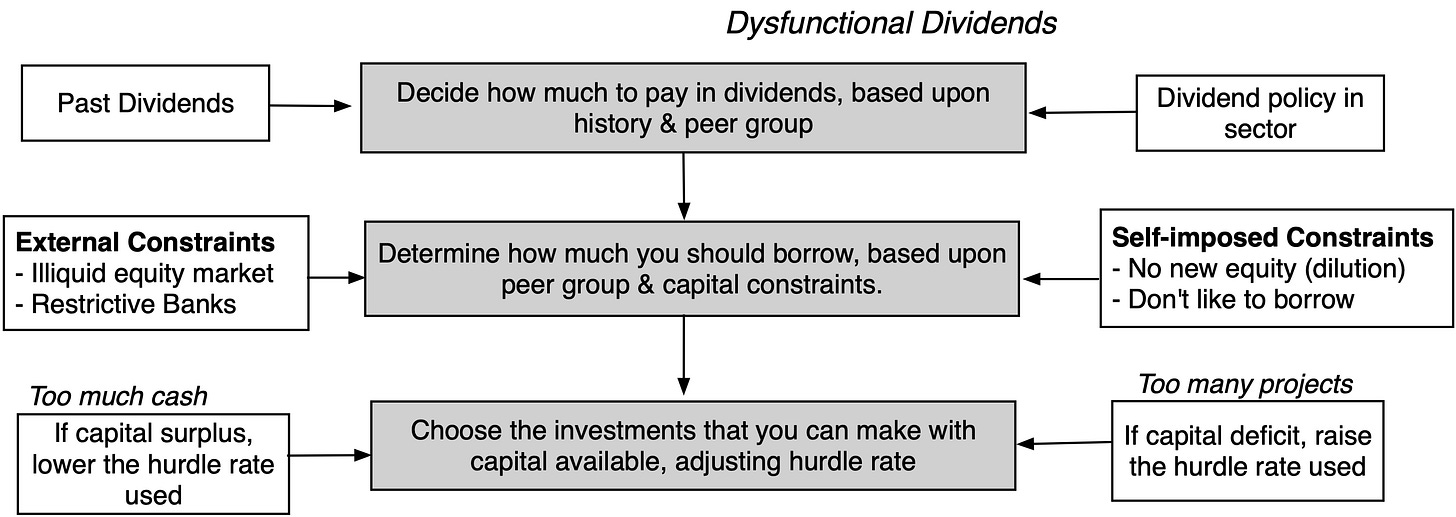

In practice, though, and especially when companies feel that they have to pay dividends, either because of their history of doing so (inertia) or because everyone else in their peer group pays dividends (me-tooism), dividend decisions startthe sequence, skewing the investment and financing decisions that follow. Thus, a firm that chooses to pay out more dividends than it should, will then turn out and either reject value-adding projects that it should have invested in or borrow more than it can afford to, and this dysfunctional dividend sequence is described below:

In this dysfunctional dividend world, some companies will pay out far more dividends than they should, hurting the very shareholders that they think that they are benefiting with their generous dividends.

Measuring Potential Dividends

In the discussion of dysfunctional dividends, I argued that some companies pay out far more dividends than they should, but that statement suggests that you can measure how much the "right" dividends should be. In this section, I will argue that such a measure not only exists, but is easily calculated for any business, from its statement of cash flows.

Free Cash Flows to Equity (Potential Dividends)

The most intuitive way to think about potential dividends is to think of it as the cash flow left over after every conceivable business need has been met (taxes, reinvestments, debt payments etc.). In effect, it is the cash left in the till for the owner. Defined thus, you can compute this potential dividend from ingredients that are listed on the statement of cash flows for any firm:

Note that you start with net income (since you are focused on equity investors), add back non-cash expenses (most notably depreciation and amortization, but including other non-cash charges as well) and net out capital expenditures (including acquisitions) and the change in non-cash working capital (with increases in working capital decreasing cash flows, and decreases increasing them). The last adjustment is for debt payments, since repaying debt is a cash outflow, but raising fresh debt is a cash inflow, and the net effect can either augment potential dividends (for a firm that is increasing its debt) or reduce it (for a firm that is paying down debt).

Delving into the details, you can see that a company can have negative free cash flows to equity, either because it is a money losing company (where you start the calculation with a net loss) or is reinvesting large amounts (with capital expenditures running well ahead of depreciation or large increases in working capital). That company is obviously in no position to be paying dividends, and if it does not have cash balances from prior periods to cover its FCFE deficit, will have to raise fresh equity (by issuing shares to the market).

FCFE across the Life Cycle

I know that you are probably tired of my use of the corporate life cycle to contextualize corporate financial policy, but to understand why dividend policies vary across companies, there is no better device to draw on.

Young companies are unlikely to return cash to shareholders, because they are not only more likely to be money-losing, but also because they have substantial reinvestment needs (in capital expenditures and working capital) to generate future growth, resulting in negative free cash flows to equity. As companies transition to growth companies, they may become money-making, but at the height of their growth, they will continue to have negative free cash flows to equity, because of reinvestment needs. As growth moderates and profitability improves, free cash flows to equity will turn positive, giving these firms the capacity to return cash. Initially, though, it is likely that they will hold back, hoping for a return to their growth days, and that will cause cash balances to build up. As the realization dawns that they have aged, companies will start returning more cash, and as they decline, cash returns will accelerate, as firms shrink and liquidate themselves.

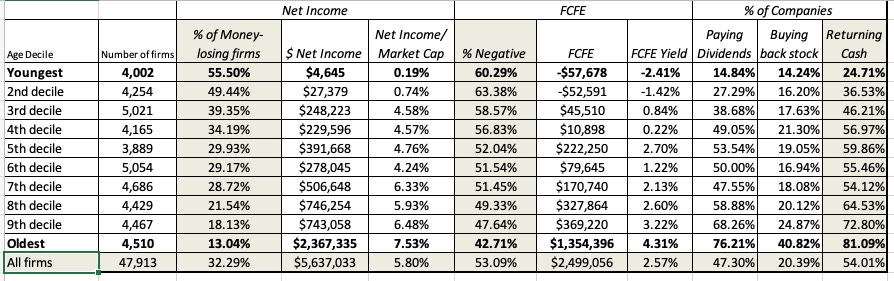

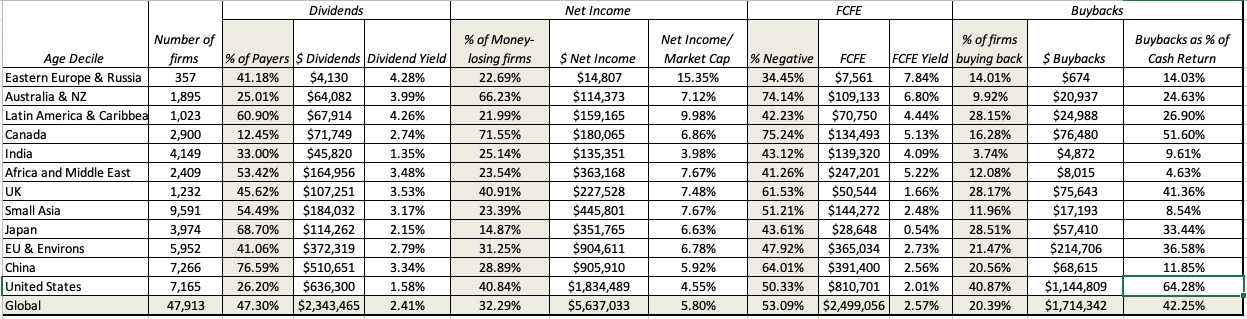

Of course, you are skeptical and I am sure that you can think of anecdotal evidence that contradicts this life cycle theory, and I can too, but the ultimate test is to look at the data to see if there is support for it. At the start of 2023, I classified all publicly traded firms globally, based upon their corporate ages (measured from the year of founding through 2022) into ten deciles, from youngest and oldest, and looked at free cash flows and cash return for each group:

As you can see, the youngest firms in the market are the least likely to return cash to shareholders, but they have good reasons for that behavior, since they are also the most likely to be money losing and have negative freee cash flows to equity. As firms age, they are more likely to be money-making, have the potential to pay dividends (positive FCFE) and return cash in the form of dividends or buybacks.

Dividends and Buybacks: Fact and Fiction

Until the early 1980s, there was only one conduit for publicly traded companies to return cash to owner, and that was paying dividends. In the early 1980s, US firms, in particular, started using a second option for returning cash, by buying back stock, and as we will see in this section, it has become (and will stay) the predominant vehicle for cash return not only for US companies, but increasingly for firms around the world.

The Facts

Four decades into the buyback surge, there are enough facts that we can extract by looking at the data that are worth highlighting. First, it is undeniable that US companies have moved dramatically away from dividends to buybacks, as their primary mode of cash return, and that companies in the rest of the world are starting to follow suit. Second, that shift is being driven by the recognition on the part of firms that earnings, even at the most mature firms, have become more volatile, and that initiating and paying dividends can trap firms into . Third, while much has been made of the tax benefits to shareholders from buybacks, as opposed to dividends, that tax differential has narrowed and perhaps even disappeared over time.

1. Buybacks are supplanting dividends as a mode of cash return

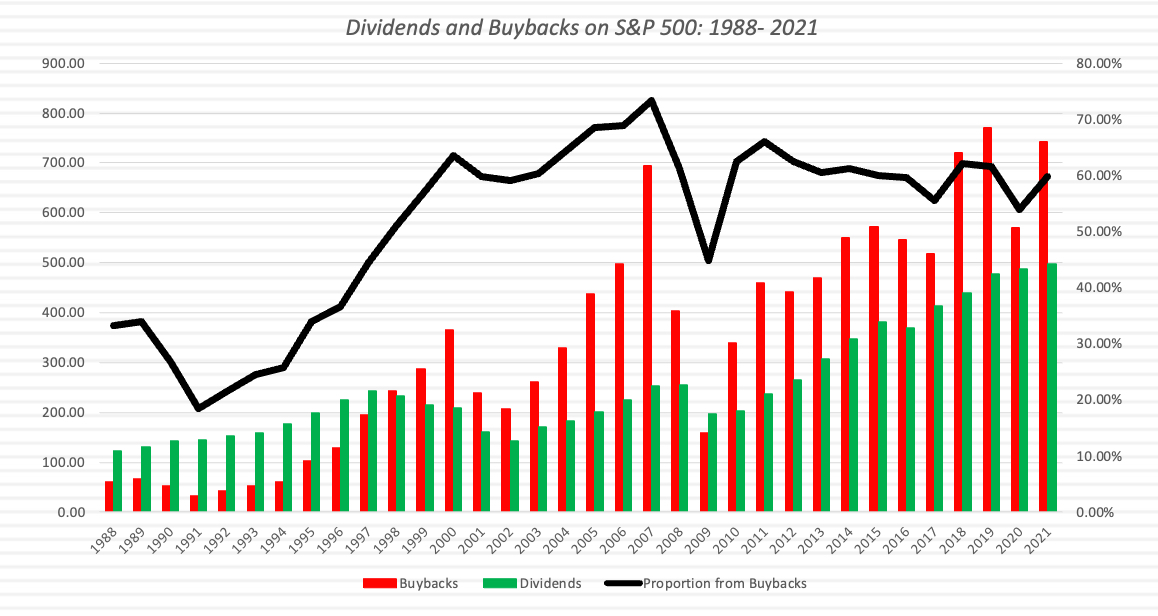

I taught my first corporate finance class in 1984, and at the time, almost all of the cash returned by companies to shareholders took the form of dividends, and buybacks were uncommon. In the graph below, you can see how cash return behavior has changed over the last four decades, and the trend lines are undeniable;

The move to buybacks started in earnest in the mid 1980s and by 1988, buybacks were about a third of all cash returned to shareholders. In 1998, buybacks exceeded dividends for the first time in US corporate history and by last year, buybacks accounted for almost two thirds of all cash returned to shareholders. In short, the default mechanism for returning cash at US companies has become buybacks, not dividends. Lest you start believing that buybacks are a US-centric phenomenon, take a look at global dividends and buybacks, in the aggregate, broken down by region in 2022:

Note that while the US is the leader of the pack, with 64% of cash returned in buybacks, the UK, Canada, Japan and Europe are also seeing a third or more of cash returned in buybacks, as opposed to dividends. Among the emerging market regions, Latin America has the highest percent of cash returned in buybacks, at 26.90%, and India and China are still nascent markets for buybacks. The shift to buybacks that started in the United States clearly has now become a global phenomenon and any explanation for its growth has to be therefore global as well.

2. Buybacks are more flexible than dividends

If you buy into the notion of a free cash flow to equity as a potential cash return, companies face a choice between paying dividends and buying back stock, and at first sight, the impact on the company of doing either is exactly the same. The same amount of cash is paid out in either case, the effects on equity are identical (in both book value and market value terms) and the operations of the company remain unchanged. The key to understanding why companies may choose one over the other is to start with the recognition that in much of the world, dividends are sticky, i.e., once initiated and set, it is difficult for companies to suspend or cut dividends without a backlash, as can be seen in this graph that looks at the percent of US companies that increase, decrease and do nothing to dividends each year:

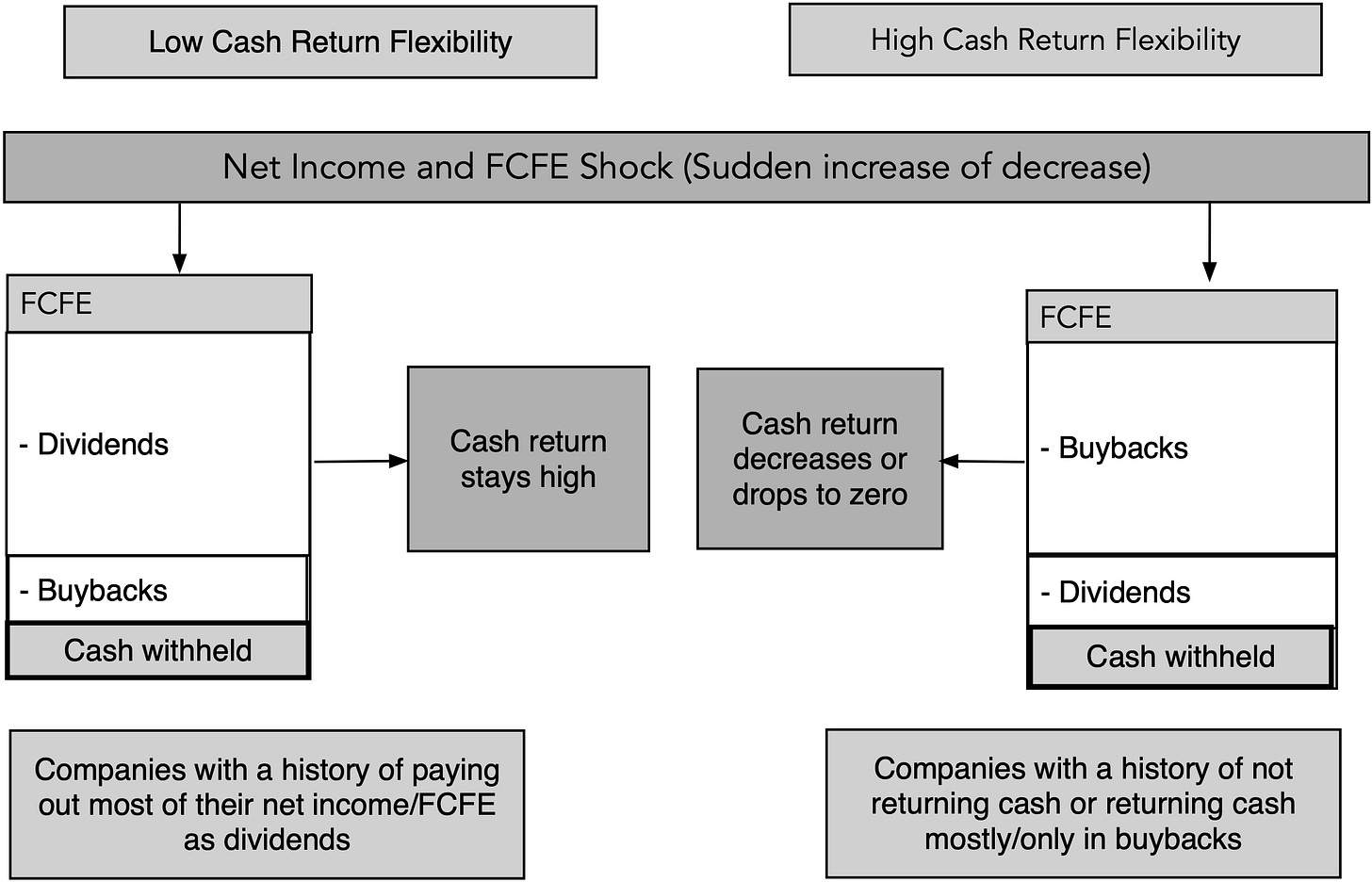

Note that the number of dividend-paying companies that leave dividends unchanged dominates companies that change dividends every single year, and that when companies change dividends, they are far more likely to increase than cut dividends. The striking feature of the graph is that even in crisis years like 2008 and 2020, more companies increased than cut dividends, testimonial to its stickiness. In contrast, companies are far more willing and likely to revisit buybacks and slash or suspend them, if the circumstances change, making it a far more flexible way of returning cash:

At the core, this flexibility is at the heart of the shift to buybacks, especially as fewer and fewer companies have the confidence that they can deliver stable and predictable earnings in the future, some because globalization has removed local market advantages and some because their businesses are being disrupted. It is true that there is a version of dividends, i.e., special dividends, that may offer the same flexibility, and it will be interesting to see if their usage increases as governments target companies buying back stock for punishment or higher taxes.

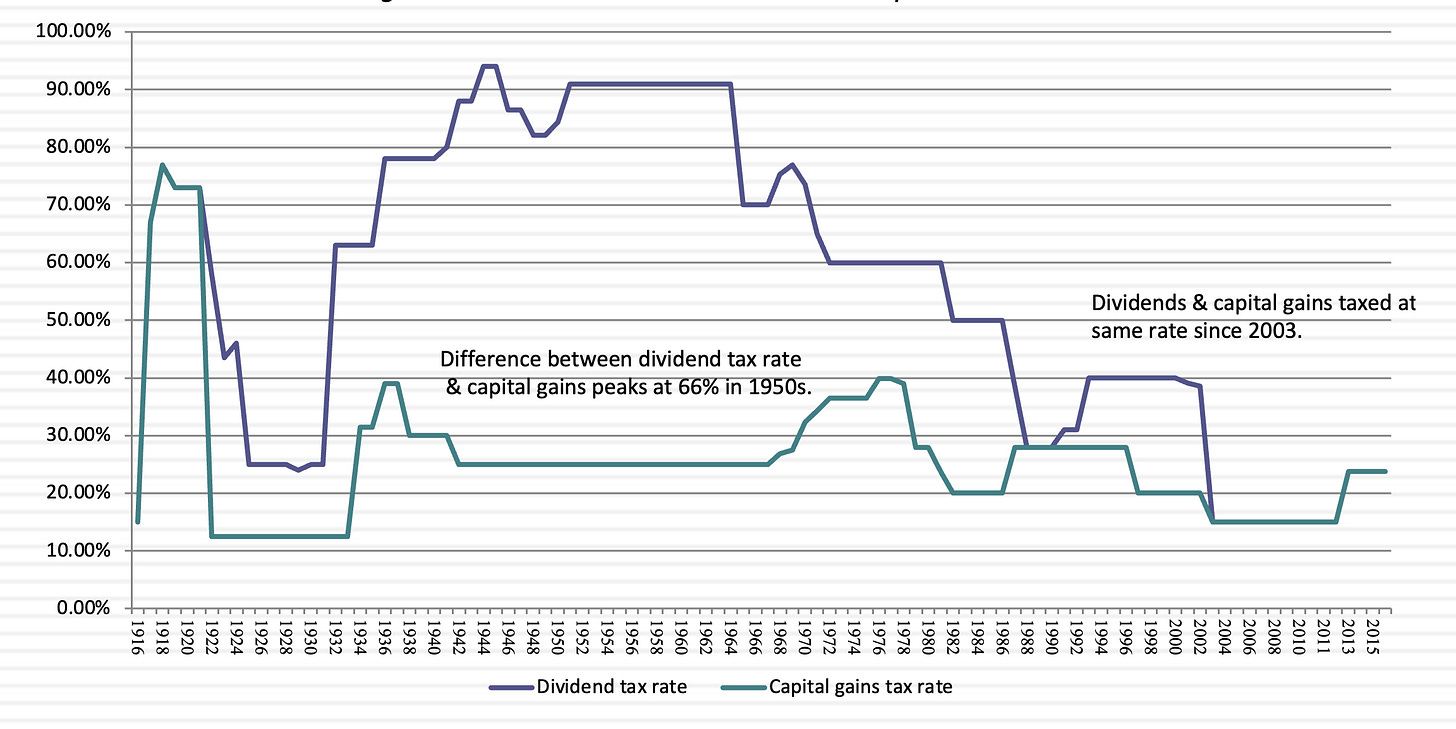

3. There are tax benefits (to shareholders) from buybacks, but they have decreased over time

From the perspective of shareholders, dividends and buybacks create different tax consequences, and those can affect which option they prefer. A dividend gives rise to taxable income in the period that it is paid, and taxpayer have little or no way of delaying or evading paying taxes. A buyback gives investors a choice, with those opting to sell back their shares receiving a realized capital gain, which will be taxed at the capital gains tax rate, or not selling them back, giving rise to an unrealized capital gain, which will be taxed in a future period, when the stock is sold. For much of the last century, dividends were taxed in the US as ordinary income, at rates much higher than that paid on capital gains.

While the differential tax benefit in the last century is often mentioned as the reason for the rise of buybacks, note that the tax differential was even worse prior to 1980, when dividends essentially dominated, to the post-1980 period, when buybacks came into vogue. For much of this century, at least in the US, dividends and buybacks have been taxed at the same rate, starting at 15% in 2003 and rising to 23.8% in 2011 (a 20% capital gains rate + 3.8% Medicare tax on all income), thus erasing much of the difference between dividends and realized capital gains for shareholder tax burdens. However, shareholders still get a benefit with unrealized capital gains that can be carried forward to a future tax-advantageous year or even passed on in inheritance as untaxed gains.

Until last year, there were no differences in tax consequences to companies from paying dividends or buying back stock, but the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 introduced a 1% tax rate on buybacks, thus creating at least a marginal additional cost to companies that bough back stock, instead of paying dividends. If the only objective of this buyback tax is raising revenues, I don't have a problem with that because it will help close the budget gap, but to the extent that this is designed to change corporate behavior by inducing companies to not buy back stock or to invest more back into businesses, it is both wrong headed and will be ineffective, as I will argue in the next section.

The Fiction

The fictions about buybacks are widespread and are driven as much by ideological blinders as they are by a failure to understand what a business is, and how to operate it. The first is that buybacks can increase or decrease the value of a business, with buyback advocates making the former argument and buyback critics the latter. They are both wrong, since buybacks can only redistribute value, not create it. The second is that surge in buybacks has been fed by debt financing, and it is part of a larger and darker picture of over levered companies catering to greedy, short term shareholders. The third is that buybacks are bad for an economy, with the logic that the cash that is being used for the buybacks is not being invested back in the business, and that the latter is better for economic growth. The final argument is that the large buybacks at US companies represent cash that is being taken away from other stakeholders, including employees and customers, and is thus unfair.

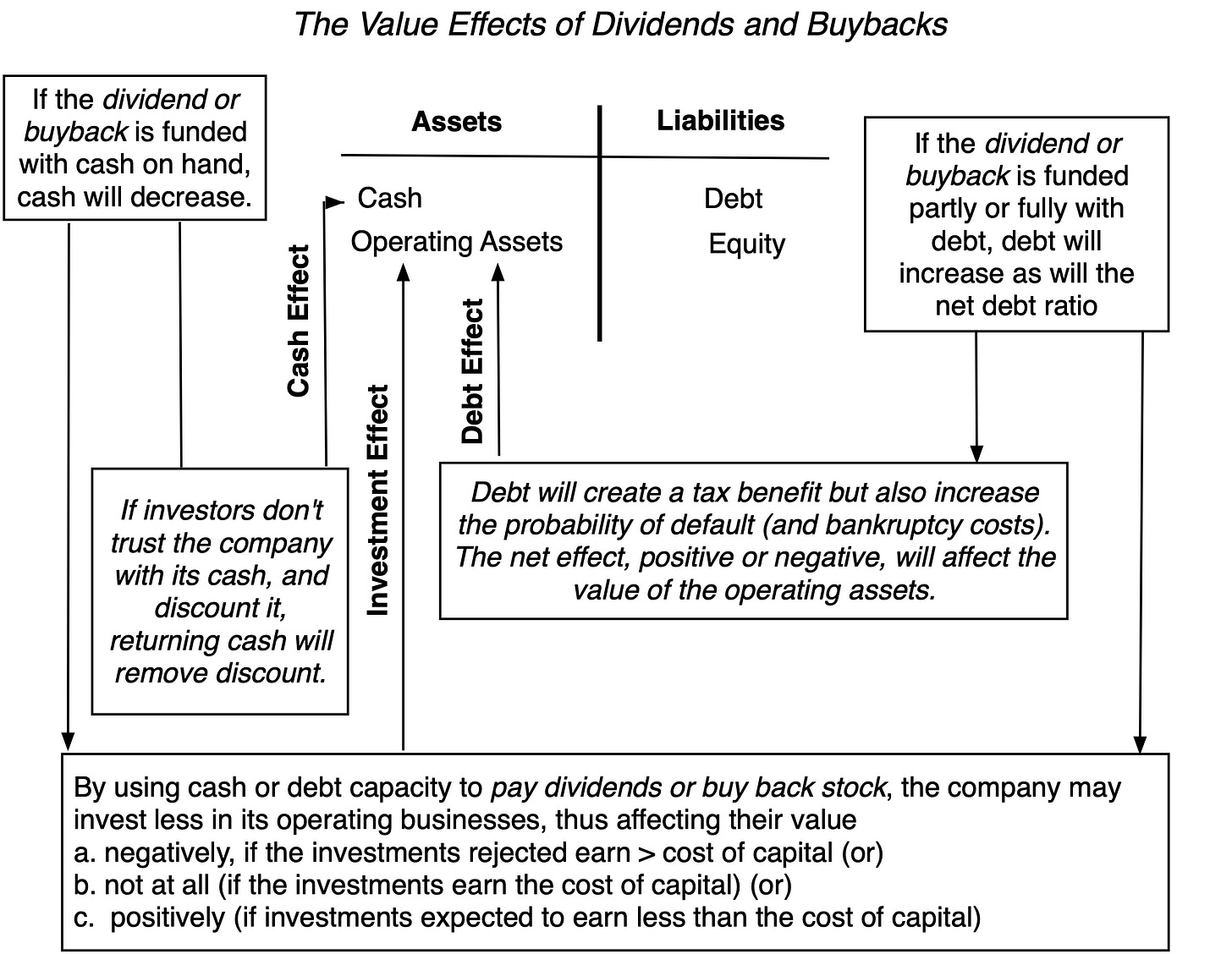

1. Buybacks increase (decrease) value

Value in a business comes from its capacity to invest money and generate cash flows into the future, and defined as such, the act of returning cash by itself, either as dividends or buybacks cannot create or destroy value. It is true that the way in which dividends and buybacks are funded or the consequences that they have for investing can have value effects, but those value effects do not come from the cash return, but from investing and financing dysfunction. The picture below captures the pathways by which the wya dividends and buybacks are funded can affect value:

The implications are straight forward and common sense. While a buyback or dividend, by itself, cannot affect value, the way it is funded and the investments that it displaces can determine whether value is added or destroyed.

Leverage effect: If a company that is already at its right mix of debt (see my last post) choose to add to that debt to fund its dividend payments or buybacks, it is hurting its value by increasing its cost of capital and exposure to default risk. However, a firm that is under levered, i.e., has too little debt, may be able to increase its value by borrowing money to fund its cash return, with the increase coming from the skew in the tax code towards debt.

Investment effect: If a company has a surplus of value-adding projects that it can take, and it chooses not to take those projects so as to be able to pay dividends or buy back stock, it is hurting it value. By the same token, a company that is in a bad business and is struggling to make its cost of capital will gain in value by taking the cash it would have invested in projects and returning that cash to shareholders.

Finally, there is a subset of companies that buy back stock, not with the intent of reducing equity and share count, but to cover shares needed to cover stock-based compensation (option grants). Thus, when management options get exercised, rather than issue new shares and dilute the ownership of existing shareholders, these companies use shares bought back to cover the exercise. The value effect of doing so is equivalent to buybacks that reduce share count, because not issuing shares each year to cover option exercises is effecting accomplishing the same objective of keeping share count lower.

There is an element where there dividends and buybacks can have contrasting effects. Dividends are paid to all shareholders, and thus cannot make one group of shareholders better or worse off than others. Buybacks are selective, since only those shareholders who sell their shares back receive the buyback price, and they have the potential to redistribute value. In what sense? A company that buys back stock at too high a price, relative to its intrinsic value, is redistributing value from the shareholders who remain in the company to those who sell their shares back. In contrast, a company that buys back shares at a low price, relative to its intrinsic value, is redistributing value from the shareholders who sell their shares back to those who stay shareholders in the firm. This is at the heart of Warren Buffet's defense of buybacks at Berkshire Hathaway as a tool, since he adds the constraint that the buybacks will continue only if they can be done at less than intrinsic value, and the assumption is that Buffet does have a better sense of the intrinsic value of his company than market participants. It is true that some companies buy back stock at the high prices, and if that is your reason, as a shareholder in the company for taking a stand against buybacks, I have a much simpler and more effective response than banning buybacks. Just sell your shares back and be on the right side of the redistribution game!

2. Buybacks are being financed with debt

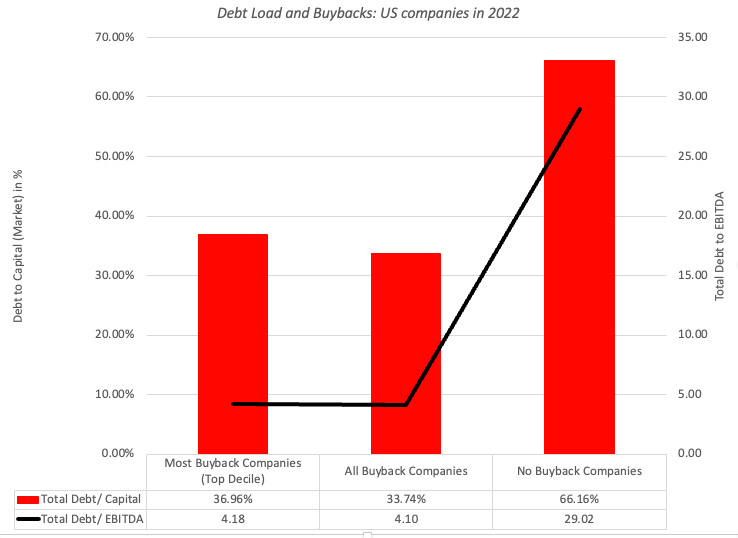

As I noted in my lead in to this section, a company that borrows money that it cannot afford to borrow to buy back stock is not just damaging its value but putting its corporate existence at risk. I have heard a few critics of buybacks contend that buybacks are being funded primarily or predominantly with debt, using anecdotal examples of companies that have followed this script, to back up their claim. But is this true across companies? To address this, I looked companies in the US (because this critique seems to be directed primarily at them), broken down by whether they did buybacks in 2022, and then examined debt loads within each group:

You can be the judge, using both the debt to capital ratio and the debt to EBITDA multiple, that companies that buy back stock have lower debt loads than companies that don't buy back stock, at odds with the "debts fund buybacks" story. Are there firms that are using debt to buy back stock and putting their survival at risk? Of course, just as there are companies that choose other dysfunctional corporate finance choices. In the cross section, though, there is little evidence that you can point to that buybacks have precipitated a borrowing binge at US companies.

3. Buybacks are bad for the economy

The final argument against buybacks has little to do with shareholder value or debt but is centered around a mathematical truth. Companies that return cash to shareholders, whether as dividends or buybacks, are not reinvesting the cash, and to buyback critics, that fact alone is sufficient to argue against buybacks. There are two premises on which this argument is built and they are both false.

The first is that a company investing back into its own business is always better for the economy than that company not investing, and that misses the fact that investing in bad businesses, just for the sake of investing is not good for either shareholders or the economy. Is there anyone who would argue with a straight face that we would be all better off if Bed Bath and Beyond had built more stores in the last decade than they already have? Alternatively, would we not all have been better served if GE had liquidated itself as a company a decade ago, when they could have found eager buyers and returned the cash to their shareholders, instead of continuing as a walking dead company?

The second is that the money returned in buybacks, which exceeded a trillion dollars last year, somehow disappeared into a black hole, when the truth is that much of that money got reinvested back into the market in companies that were in better businesses and needed capital to grow? Put simply, the money got invested either way, but by companies other than GE and Bed Bath and Beyond, and that counts as a win for me.

Watching the debate on buybacks in the Senate last year, I was struck by how disconnected senators were from the reality of buybacks, which is that they bulk of buybacks come from companies that have no immediate use for the money, or worse, bad uses for the monty, and the effect of buybacks is that this money gets redirected to companies that have investment opportunities and operate in better businesses.

4. Buybacks are unfair to other stakeholders

If the argument against buybacks is that the money spent on buybacks could have been spent paying higher wages to employees or improving product quality, that is true. That argument is really one about how the pie is being split among the different shareholders, and whether companies are generating profits that excessive, relative to the capital invested. I argued in my fifth data post that if there is backing for a proposition, it is that companies are not earning enough on capital invested, not that they are earning too much. I will wager that if you did break down pay per hour or employee benefits, they will be much better at companies that are buying back stock than at companies that don't. Unfortunately, I do not have access to that data at the company-level on either statistic, but I am willing to consider evidence to the contrary.

The Bottom Line

It is telling that some of the most vehement criticism of buybacks come from people who least understand business or markets, and that the legislative solutions that they craft reflect this ignorance. Taxing buybacks because you are unable to raise corporate tax rates may be an effective revenue generator for the moment, but pushing that rate up higher will only cause the cash return to take different forms. Just as the attempts to curb top management compensation in the early 1990s gave rise to management options and a decade of even higher compensation, attempts to tax buybacks may backfire. If the end game in taxing buybacks is to change corporate behavior, trying to induce invest more in their businesses, it will be for the most part futile, and if it does work, will do more harm than good.

YouTube Video

Data Links

Data Update Posts for 2023