Deja Vu In Turkey: Currency Crisis and Corporate Insanity!

This has been a year of rolling crises, some originating in developed markets and some in emerging markets, and the market has been remarkably resilient through all of them. It is now Turkey's turn to be in the limelight, though not in a way it hoped to be, as the Turkish Lira enters what seems like a death spiral, that threatens to spill over into other emerging markets. There is plenty that can be said about the macro origins of this crisis, with Turkey's leaders and central bank bearing a lion's share of the blame, but that is not going to be the focus of this post. Instead, I would like to examine how Turkish business practices, and the willful ignorance of basic financial first principles, are making the effects of this crisis worse, and perhaps even catastrophic.

The Turkish Crisis: So far!

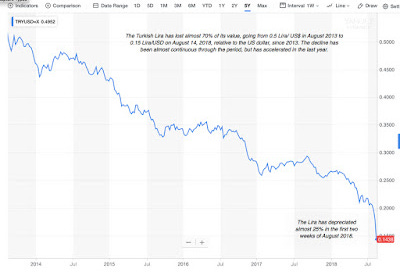

The Turkish problem became a full fledged crisis towards the end of last week, but this is a crisis that has been brewing for months, if not years. It has its roots in both Turkish politics and dysfunctional practices on the part of Turkish regulators, banks and businesses, and has been aided and abetted by investors who have been too willing to look the other way. The most visible symbol of this crisis has been the collapse of the Turkish Lira, which has been losing value, relative to other currencies, for a while, capped off by a drop of almost 15% last Friday (August 10):

Yahoo! FinanceWhile it is undoubtedly true that the weaker Lira will lead to more problems, currency collapses are symptoms of fundamental problems and for Turkey, those problems are two fold. One is a surge in inflation in the Turkish economy, which can be seen in graph below:

While it easy to blame the Turkish central bank for dereliction of duty, it has been handicapped by Turkey's political leadership, which seems intent on making its own central bank toothless. Rather than allow the central bank to use the classic counter to a currency collapse of raising central bank-set interest rates, the government has put pressure on the bank to lower rates, with predictable (and disastrous) consequences.

Corporate Finance: First Principles

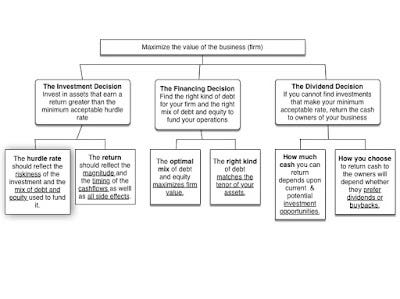

I teach both corporate finance and valuation, and while both are built on the same first principles, corporate finance is both wider and deeper than valuation since it looks at businesses from the inside out. i.e., how decisions made a firm's founders/managers play out in value. In my introductory corporate finance class, I list out the three common sense principles that govern all businesses and how they drive value:

The financing principle operates at the nexus of investing and dividend principles and choices you make on financing can affect both investment and dividend policy. It is true that when most analysts look at the financing principle, they zero in on the financing mix part, looking at the right mix of debt and equity for a firm. I have posted on that question many times, including the start of this year as part of my examination of global debt ratios, and have used the tools to assess whether a company should borrow money or use equity (See my posts on Tesla and Valeant). There is another part to the financing principle, though, that is often ignored, and it is that the right debt for a company should mirror its asset characteristics. Put simply, long term projects should be funded with long term debt, convertible debt is a better choice than fixed rate debt for growth companies and assets with cash flows in dollars (euros) should be funded with dollar (euro) debt. The intuition behind matching does not require elaborate mathematical reasoning but is built on common sense. When you mismatch debt (in terms of maturity, type or currency) with assets, you increase your likelihood of default, and holding debt ratios constant, your cost of debt and capital.

In effect, your perfect debt will provide you with all of the tax benefits of debt while behaving like equity, with cash flows that adapt to your cash flows from operations.

There are two ways that you can match debt up to assets. The first is to issue debt that is reflective of your projects and assets and the second is to use derivatives and swaps to fix the mismatch. Thus, a company that gets its cash flows in rupees, but has dollar debt, can use currency futures and options to protect itself, at least partially, against currency movements. While access to derivatives and swap markets has increased over time, a company that knows its long term project characteristics should issue debt that matches that long term exposure, and then use derivatives & swaps to protect itself against short term variations in exposure.

Turkey: A Debt Mismatch Outlier?

The argument for matching debt structure (maturity, currency, convertibility) to asset characteristics is not rocket-science but corporations around the world seem to revel in mismatching debt and assets, using short term debt to fund long term assets (or vice versa) and sometimes debt in one currency to fund projects that generate cashflows in another. In numerous studies, done over the decades, looking across countries, Turkish companies rank among the very worst, when it comes to mismatching currencies on debt, using foreign currency debt (Euros and dollars primarily) to fund domestic investments.

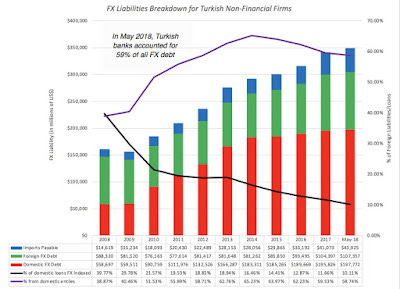

Lest I be accused of using foreign data services that are biased against Turkey, I decided to stick with the data provided by the Turkish Central Bank on the currency breakdown of borrowings by Turkish firms. In the chart below, I trace the foreign exchange (FX) assets and liabilities, for non-financial Turkish companies, from 2008 and 2018:

The numbers are staggeringly out of sync with Turkish non-financial service companies owing $217 billion more in foreign currency terms than they own on foreign currency assets, and this imbalance (between foreign exchange assets and liabilities) has widened over time, tripling since 2008.

I am sure that there will be some in the Turkish business establishment who will blame the mismatching on external forces, with banks in other European countries playing the role of villains, but the numbers tell a different story. Much of the FX debt has come from Turkish banks, not German or French banks, as can be seen in the chart below:

In 2018, 59% of all FX liabilities at Turkish non-financial service firms came from Turkish banks and financial service firms, up from 39% in 2008. The mismatch is not just on currencies, though. Looking at the breakdown, by maturity, of FX assets and liabilities for Turkish non-financial service firms, here is what we see:

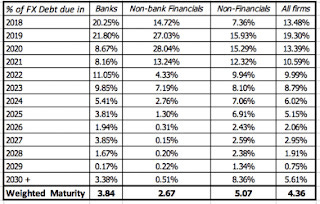

In May 2018, while about 80% of FX assets are Turkish non-financial firms are short term, only 27% of the FX debt is short term, a large temporal imbalance.

It is possible that the Turkish government may be able to put pressure on domestic banks to prevent them from forcing debt payments, in the face of the collapse of the lira, but looking at when the debt owed foreign borrowers comes due (for both Turkish financial and non-financial firms), here is what we see.

From a default risk perspective, though, the debt maturity schedule carries a message. About 50% of debt owed by Turkish banks and 40% of the debt owed by Turkish non-financial service companies will be coming due by 2020, and if the precipitous drop in the Lira is not reversed, there is a whole lot of pain in store for these firms.

Rationalizing the Mismatch: The Good, The Dangerous and the Deadly

Turkish firms clearly have a debt mismatch problem, and the institutions (government, bank regulators, banks) that should have been keeping the problem in check seem to have played an active role in making it worse. Worse, this is not the first time that Turkish firms and banks will be working through a debt mismatch crisis. It has happened before, in 1994, 2001 and 2008, just looking at recent decades. If insanity is doing the same thing over and over, expecting a different outcome, there is a good case to be made that Turkish institutions, from top to bottom, are insane, at least when it comes to dealing with currency in financing. So, why do Turkish companies seem willing to repeat this mistake over and over again? In fact, since this mismatching seems to occur in many emerging markets, though to a lesser scale, why do companies go for currency mismatches? Having heard the rationalizations from dozens of CFOs on every continent, I would classify the reasons on a spectrum from acceptable to absurd.

Acceptable Reasons

There are three scenarios where a company may choose to mismatch debt, borrowing in a currency other than the one in which it gets its cash flows.

The mismatched debt is subsidized: If the mismatched debt is being offered to you (the borrower) at rates that are well below what you should be paying, given your default risk, you should accept that mismatched debt. That is sometimes the case when companies get funding from organizations like the IFC that offer the subsidies in the interests of meeting other objectives (such as increasing investment in under developed countries). It can also happen when lenders and bondholders become overly optimistic about an emerging market's prospects, and lend money on the assumption that high growth will continue without hiccups.

Domestic debt markets are moribund: There are emerging markets where the only option for borrowing money is local banks, and during periods of uncertainty or crisis, these banks can pull back from lending. If you are a company in one of these markets and have the option of borrowing elsewhere in the world to fund what you believe are good investments, you may push forward with your borrowing, even though it is currency mismatched.

Domestic debt markets are too rigid: As you can see from the debt design section, the perfect debt for your firm will often require tweaks that include not only conversion and floating rate options, but more unusual tweaks (such as commodity-linked interest rates). If domestic debt markets are unwilling or unable to offer these customized debt offerings, a company that can access bond markets overseas may do so, even if it means borrowing in a mismatched currency.

In all three cases, though, once the money has been borrowed, the company that has mismatched its debt should turn to the derivatives and swap markets to reduce or eliminate this mismatch.

Dangerous Reasons

There are two reasons that are offered by some companies that mismatch debt that may make sense, on the surface, but are inherently dangerous:

Speculate on currency: Mismatching currencies, when you borrow money, can be a profitable exercise, if the currency moves in the right direction. A Turkish company that borrows in US dollars, a lower-inflation currency with lower interest rates, to fund projects that deliver cashflows in Turkish Lira, a higher-inflation currency, will book profits if the Lira strengthens against the US dollar. Since emerging market currencies can go through extended periods of deviation from purchasing power parity, i.e., the higher inflation emerging market currency strengthens (rather than weakening) against the lower inflation developed market currency, mismatching currencies can be profitable for extended periods. There will be a moment of reckoning, in the longer term, though, when exchange rates will correct, and unless the company can see this moment coming and correct its mismatch, it will not only lose all of the easy profits from prior periods, but find its survival threatened. Currency forecasting is a pointless exercise, even when practiced by professional currency traders, and I think that companies should steer away from the practice.

Everyone does it: I have argued that many corporate finance practices are driven by inertia and me-tooism rather than good sense, and in many countries where currency mismatches are common, the standard defense is that everyone does it. Many of these companies argue that the government cannot let the entire corporate sector slide into default and will step in to bail them out, and true to form, governments deliver those bailouts. In effect, the taxpayers become the backstop for bad corporate behavior.

Bad Reasons

I am surprised by some of the arguments that I have heard for mismatching debt, since they suggest fundamental gaps in basic financial and economic knowledge.

The mismatched debt has a lower interest rate: I have heard CFOs of companies in emerging markets, where domestic debt carries high interest rates, argue that it is cheaper to borrow in US dollars or Euros, because interest rates are lower on loans denominated in those currencies. After all, it is cheaper to borrow at 5% than at 15%, right? Not necessarily, if the 5% rate is on a US dollar debt and the 15% debt is in Turkish Lira, and here is why. If the expected inflation rate in US dollars is 2% and in Turkish Lira is 14%, it is the Turkish Lira debt that is cheaper.

Risk/Reward: There are some companies that fall back on the proposition that mismatching debt is like any other financial choice, a trade off between higher risk and higher reward. In other words, their belief is that they will earn higher profits, on average and over time, with mismatched debt than with matched debt, but with more variability in those profits. This argument stems from the misplaced belief that markets reward all risk taking, when the truth is that senseless risk taking just delivers more risk, with no reward, and mismatching debt is senseless.

The Fix

It is too late for Turkish companies to fix their debt problem for this crisis, but given that this crisis too shall pass, albeit after substantial damage has been done, there are actions that we can take to keep it from repeating, though it will require everyone involved to change their ways:

Governments should stop enabling debt mismatching, by not stepping in repeatedly to save corporates that have mismatched debt. That will increase the short term pain of the next crisis, but reduce the likelihood of repeating that crisis.

Bank Regulators should measure how much the banks that they regulate have lent out to corporates, in mismatched debt, and require them to set aside more capital to cover the inevitable losses. That, in turn, will reduce the profitability of lending out money to companies that mismatch.

Banks have to incorporate whether the debt being taken by a business is mismatched in deciding how much to lend and on what terms. The interest rates on mismatched debt should be higher than on matched debt.

Companies and businesses have to consider what currency a loan or bond is in, when evaluating interest rates, and in their own best interests, try to match up debt to assets, either directly (in debt design) or using derivatives.

Investors in companies should start breaking down the profitability of firms with mismatched debt, especially in good periods, into profits from debt mismatch and profits from operations, and ignore or at least discount the former, when pricing these companies.

I don't think any of these changes will happen overnight but unless we change our behavior, we are designed to replay this crisis in other emerging markets repeatedly.

YouTube Video

Data

Papers