Managing across the Corporate Life Cycle: CEOs and Stock Prices!

One of the big news stories of last week was Jack Dorsey stepping down as CEO of Twitter, and the market's response to that news was to push up Twitter's stock price by almost 10%. That reaction suggested, at least for the moment, that investors believed that Twitter would be better off without Dorsey running it, a surprise to those in the founder-worship camp. As the debate starts about whether Dorsey's hand-picked successor, Parag Agrawal, is the right person to guide Twitter through its next few years, I decided to revisit a broader question of what it is that makes for a "great CEO" and how there is no one right answer to that question, because it depends on the company, and where it stands in its life cycle. In the process, I will also look at the thorny issue of what happens when there is a mismatch between a company and its CEO, either because the board picks the wrong candidate for the job or because the company has changed over time, and the CEO has not. Finally, I will use the framework to look at the relationships between founders and their companies, and how mishandling management transitions can have damaging, perhaps even devastating, consequences for value.

The "Right" CEO: A Corporate Life Cycle Perspective

The notion that there is a collection of characteristics that makes a person a great CEO for a company, no matter what its standing, is deeply held and fed into by both academics and practitioner. In this section, I will begin by looking at the mythology behind this push, and why it does not hold up to common sense questioning.

The Mythology of the Great CEO

Are there a set of qualities that make for a great CEO? To answer the question, I looked at two institutions, one academic and one practice-oriented, that are deeply invested in that idea, and spend considerable time advancing it.

The first is the Harvard Business School, where every student who enters the MBA program is treated as a CEO-in-waiting, notwithstanding the reality that there are too few openings to accommodate that ambition. The Harvard Business Review, over the years, has published multiple articles about the characteristics of the most successful CEOs, and this one for instance, highlights four characteristics that they share in common: (a) deciding with speed and conviction, (b) engaging for impact with employees and the outside world (c) adapting proactively to changing circumstances and (d) delivering reliably.

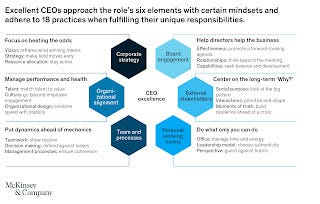

The second is McKinsey, described by some as a CEO factory, because so many of its consultants go on to become CEOs of their client companies. In this article, McKinsey lists the mindsets and practices of the most successful CEOs in the following picture:

Given how influential these organizations are in framing public perception, it is no surprise that most people are convinced that there is a template for a great CEO that applies across companies, and that boards of directors in search of new CEOs should use this template.

That perspective also gets fed by books and movies about successful CEOs, real or imagined. Consider Warren Buffett, Jack Welch and Steve Jobs, very different men who have been mythologized in the literature, as great CEOs. Many of the books about Buffett read more like hagiographies than true biographies, given how star struck the writers of these books are about the man, but by treating him as a deity, they do him a disservice. The fall of GE has taken some of the shine from Jack Welch's star, but at his peak, just over a decade ago, he was viewed as someone that CEOs should emulate. With Steve Jobs, the picture of an innovative, risk-taking disruptor comes not just from books about the man, but from movies that gloss over his first, and rockier, stint as founder-CEO of Apple in the 1980s.

The problem with the one-size-fits-all great CEO model is that it does not hold up to scrutiny. Even if you take the HBR and McKinsey criteria for CEO success at face value, there are three fundamental problems or missing pieces. First, even if all successful CEOs share the qualities listed in the HBR/McKinsey papers, not all people or even most people with these qualities become successful CEOs. So, is there a missing ingredient that allowed them to succeed? If so, what is it? Second, I find it odd that there are no questionable qualities listed on the successful CEO list, especially given the evidence that over confidence seems to be a common feature among CEOs, and that it is this over confidence that allows them to take act decisively and adopt long term perspectives. When those bets, often made in the face of long odds, pay off, the makers of those bets will be perceived as successful, but when they do not, the decision makers are consigned to the ash heap of failure. Put simply, it is possible that the quality that binds together successful CEOs the most is luck, a quality that neither Harvard Business School nor McKinsey can pass on. Third, there are clearly some successful CEOs who not only do not possess many of the listed qualities, but often have the inverse. If you believe that Elon Musk and Marc Benioff, CEOs of Tesla and Salesforce, are great CEOs, how many of the Harvard/McKinsey criteria would they possess?

The Corporate Life Cycle

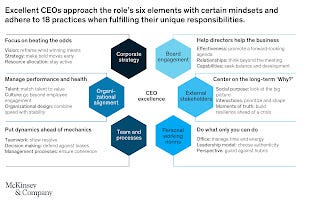

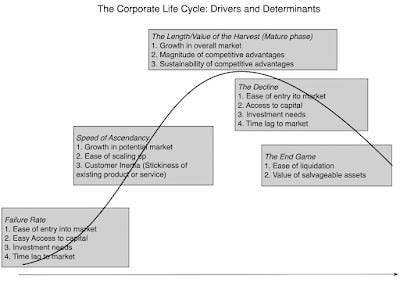

I believe that the discussion of what makes for a great CEO is flawed for a simple reason. There is no one template that works for all companies, and one way to see why is to bring in the notion that companies go through a life cycle, from start-ups (at birth) to maturity (middle age) to decline (old age). At each stage of the life cycle, the focus in the company changes, as do the qualities that top managers have to bring for success:

Early in the life cycle, as a company struggles to find traction with a business idea that meets an unmet demand, you need a visionary as a CEO, capable of thinking outside the box, and with the capacity to draw employees and investors to that vision. In converting an idea to a product or service, history suggests that pragmatism wins out over purity of vision, as compromises have to be made on design, production and marketing to convert an idea company into a business. As the products/services offered by the company scale up, the capacity to build businesses becomes front and center, as production facilities have to be built, and supply chains put in place, critical for business success, but clearly not as exciting as selling visions. Once the initial idea has become a business success, the needs to keep scaling up may require coming up with extensions of existing product lines or geographies to grow, where an opportunistic, quick-acting CEO can make a difference. As companies enter the late phases of middle age, the imperative will shift from finding new markets to defending existing market share, in what I think of the trench warfare phase of a company, where shoring up moats takes priority over new product development. The most difficult phase for a company is decline, as the company is dismantled and its sells or shuts down its constituent parts, since any one who is put in charge of this process has only pain to mete out, and bad press, to go with it. Have you ever read a book or seen a movie about a CEO who shrunk his or her company, where that person is painted as anything but a villain? In fact, I used "Larry the Liquidator" as my moniker for that CEO, to pay homage to one of my favorite movies of all time, "Other People's Money":

As you watch the video, note that the CEO of the company, under activist attack, is played by Gregory Peck (the distinguished gray-haired gentleman who sits down at the start of the video), who presumably embodies all the qualities that Harvard and McKinsey believe embody a great CEO, and Danny DeVito plays "Larry the Liquidator". Talk about type casting, but this company needs more DeVito, less Peck!

Mismatches, Transitions and Turnover

If you buy into my structure of a corporate life cycle, and how the right CEO for a company will change as the company ages, you can already see the potential for mismatches between companies and CEOs, for three reasons.

A Hiring Mistake: The first is that the board of directors for a company seeking a new CEO hires someone who is viewed by many as a successful CEO, but whose success came at a company at a very different stage in its life cycle. I think Uber dodged the bullet in 2017, when they decided not to hire Jeff Immelt as CEO for the company. Even if you had believed that Immelt was successful at his prior job as CEO for GE, and that is arguable, he would have been a horrifically bad choice as CEO at Uber, a company that is as different from GE as you can get, in every aspect, not just corporate age.

A Gamble on Rebirth: The second is when a board of director picks a mismatched CEO intentionally, with the hope that the CEO characteristics rub off on the company. This is often the case when you have a mature or declining company that thinks hiring a visionary as a CEO will lead to reincarnation as a growth company. While the impulse to become young again is understandable, the odds are against this gamble working, leaving the CEO tarnished and company worse off, in the aftermath. It was the reason that Yahoo! hired Marissa Mayer as a CEO in 2012, hoping that her success at Google would rub off on the company, an experiment that I argued would not end well for either party (and it did not).

A Changing Business; The third is a more subtle problem, where a company is well matched to its CEO at a point in time, but then evolves across the life cycle, but the CEO does not. Using the Uber example again, Travis Kalatnick, a visionary and rule breaker, might have been the best match for Uber as a company, in early years, when it was disrupting a highly regulated business (taxi cabs), but even without his personal missteps, he was ill-suited to a company that faced a monumental task of converting a model built on acquiring new riders into one that generated profits in 2017.

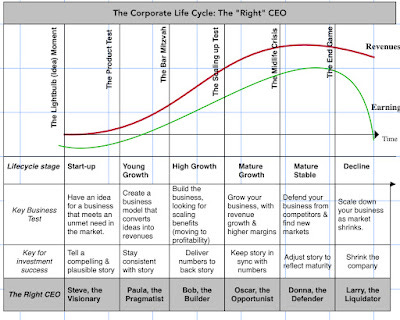

In NY case, a CEO/company mismatch is a problem, though the consequences can range from benign to malignant.

In the most benign case, a mismatched CEO recognizes the mismatch, sets ego aside and finds a partner or co-executive with the skills needed for the company. In my view, and many of you may disagree with me, the difference between the first iteration of Steve Jobs, where he let his vision run riot and almost destroyed Apple as a company, and the second iteration, where he led one of the most impressive corporate turnarounds in history, was his choice of Tim Cook as his chief operating officer in his second go-around and his willingness to delegate operating authority. In short, Jobs was able to continue to put his visionary skills to work, while Cook made sure that the promises Jobs made were delivered as products on the ground. In the most malignant form, a badly mismatched CEO is entrenched in his or her position, perhaps because the board of directors has become a rubber stamp or by tilting voting rules (shares with different voting rights) in favor of incumbency, and continues on a pathway that takes the company to ruin. In the intermediate case, the board of directors, perhaps with a push from activist investors and large stockholders, engineers a CEO change, albeit after some or a great deal of damage has been done.

The Compressed Life Cycle: Implications for Founder CEOs

It is a testimonial to how much technology companies have changed the economy and the market that some of the best-recognized names in business are those of the founders of successful technology company. I would wager that almost everyone has heard of Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, and that very few would recognize the names of Mary Barra (CEO of GM) or Darren Woods (CEO of Exxon Mobil). While there are some who venerate these founders, in what can only be called founder worship, there are others who have a more jaundiced view of them, both as human beings and as CEOs. The corporate life cycle framework provides a useful structure to think about how the technology companies, that dominate the twenty first century business landscape, are different from the manufacturing companies of the last century, and why these differences can create more management tensions at these companies.

Aging in Dog Years?

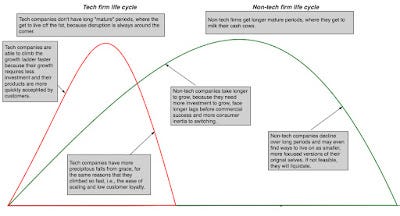

While every company goes thought the process of starting up, aging and eventually declining, the speed at which it does will vary depending on the business it is in. More specifically, the more capital it takes to enter a business and the more inertia there is among the existing players (producers, customers) are, the longer it will take for a company to get from start up to mature growth, but the same forces will play out in reverse, allowing the company to stay mature for a lot longer and decline a lot more gradual:

The great companies of the twentieth century took decades to ramp up, facing big infrastructure investments and long lags before expansion, had long stints as mature firms, milking cash flows, before embarking on long and mostly gradual declines. To illustrate, Sears and GE had century-long runs as successful companies, before time and circumstances caught up with them, and GM and Ford struggled for three decades setting up manufacturing capacity and tweaking their product offerings, before enjoying the fruits of their success. In contrast, consider Yahoo!, a company that was founded in 1994, that managed to reach a hundred billion in market capitalization by the turn of the century, enjoyed a few years of dominance, before Google's arrival and conquest of the market, before finally being acquired by Verizon in 2017. This compression of the life cycle has played out in tech company after tech company and the graph below captures the difference:

In short, tech companies age in dog years, with a 20-year tech company often resembling a hundred-year old manufacturing company, with creaky business models and facing disruption.

Implications for Founder CEOs and Management Turnover

Companies have always had founders, and while the conflict between founders and others in the company have been around for decades, the compressed life cycle has exacerbated these tensions and magnified problems. In particular, the research on founder CEOs has yielded two disparate findings. The first is that in the early stages of companies, founder CEOs either step down or are pushed out at much higher rates than in more established companies. The second is that those founder CEOs who nurse their companies to more established status, and to public offerings, are more entrenched that their counterparts at mature companies.

To understand the first phenomenon, i.e., the high displacement rate among founder CEOs of very young companies, I will draw on the work of Noah Wasserman at Harvard Business School who has focused intensively on this topic. Using data on top management turnover at young firms, many of them non-public, he concludes that almost 30% of CEOs at these firms are replaced within a few years of inception, usually at the time of new product development or fresh financing. Much of this phenomenon can be explained by venture capitalists, with large stakes, pushing for change in these companies, but a portion of it is voluntary, and to explain why a founder CEO might willingly step down, Wasserman uses the concept of the founder's dilemma, where founders trade off full control of a much less valuable firm (with themselves in control) for lesser control of a much more valuable firm (with someone else at the helm). In the corporate life cycle structure, it is a recognition on the part of founders or capital providers that the skills needed to take a company forward require a different person at the top of the organization, especially as a firm transitions from one stage of the life cycle to the next.

The founders who do manage to stay at the helm of companies that make it through to early growth status are put on a pedestal, relative to CEOs of established companies. While that may be understandable, in some cases, it can take the form of founder worship, where founders are viewed as untouchable, and any challenge to their authority is viewed as bad, leading to efforts to change the rules of the game to prevent these challenges. In the United States, where prior to 2004, it was unusual to see shares with different voting rights in the same firm, it is now more the rule than the exception in many tech companies.

Endowing CEOs with increased powers to fend off challenges seems like a particularly bad idea at tech companies, since their compressed life cycles are likely to create more, rather than less, mismatches between companies and their founder/CEOs, and sooner, rather than later. To see, why consider how corporate governance played out at Ford, a twentieth century corporate giant. Henry Ford, undoubtedly a visionary, but also a crank on some dimensions, was Ford's CEO from 1906 to 1945. His vision of making automobiles affordable to the masses, with the Model T, was a catalyst in Ford's success, but by the end of his tenure in 1945, his management style was already out of sync with the company. With Ford, time and mortality solved the problem, and his grandson, Henry Ford II, was a better custodian for the firms in the decades that followed. Put simply, when a company lasts for a century, the progression of time naturally takes care of mismatches and succession. In contrast, consider how quickly Blackberry, as a company, soared, how short its stay at the top was and how steep its descent was, as other companies entered the smart phone business. Mike Lazaridis, one of the co-founders of the company, and Jim Balsillie, the CEO he hired in 1992 to guide the company, presided over both its soaring success, gaining accolades for their management skills for doing so, and over its collapse, drawing jeers from the same crowd. By the time, the change in top management happened in 2012, it was viewed as too little, too late.

In my view, the next decade will bring forth more conflict, rooted in the compressed life cycle of companies. If I were a case study writer, and thank God I am not, I would not rush to write case studies or books about successful tech company CEOs, because many of those same CEOs will become case studies of failure within a few years. If I am an investor, I would worry more than ever before about giving up voting power to founder/CEOs, even if they are well regarded, because today's star CEO can become tomorrow's problem. I wonder whether the way Facebook has dealt with its privacy and related problems over the last few years would have been different, if investors had not allowed Mark Zuckerberg to effectively control 57% of the voting rights with less than 20% of the outstanding shares. It is worth noting that Twitter was one of the few social media companies that chose not to split its voting rights across shares, and that may explain the Jack Dorsey departure.

Implications for Investors

I have long argued that when investing in young tech companies, you are investing in a story about the company, not an extrapolation of numbers. The compressed corporate life cycle, and the potential for CEO/company mismatches that it creates, adds a layer of additional uncertainty to valuation. In short, when assessing the value of a young company's story, you are also assessing the capacity of the management of the company to deliver on that story. To the extent that the founder is the lead manager, and the narrative-setter, any concerns you have about the founder's capacity to convert that story into business success will translate into lower value. Let me illustrate using three examples, the first being Amazon in my early valuations of the company between 1997 and 2000, the second being Twitter, especially in the context of Jack Dorsey's departure and Paytm, the Indian online company, whose recent IPO was a dumpster fire.

I have always liked Amazon, as a company, and one reason for that was Jeff Bezos. Many younger investors are surprised when I tell them that Bezos was not a household name for much of Amazon's early rise, and that it was The Washington Post acquisition in 2013 that brought him into public view. One reason that I attached lofty values to Amazon as a company, even when it was a tiny, money-losing company was that Bezos not only told the same story, one that I described as Field of Dreams story, where if you build it (revenues), they (profits) will come. but acted consistently with that story. He built a management team that believed that story and trusted them to make big decisions for the company, thus easing the transition from small, online book retailer to one of the largest companies in the world. It is a testimonial to Bezos' success in transitioning management that Amazon's value as a company today would be close to the same, with or without him at the helm, explaining why the announcement that he was stepping down as CEO on July 5 created almost no impact on the stock price.

I valued Twitter for the first time, just ahead of its IPO in 2013, and built a model premised on the assumption that the company would find a way to monetize its larger user base and build a consistently money-making enterprise. In the years since, I have been frustrated by its inability to make that happen, and in this post in 2015, I laid the blame at least partially at the feet of Twitter's management, contrasting its failure to Facebook's success. I don't know Jack Dorsey, and I wish him well, but in my view, his skill set seemed ill suited to what Twitter needed to succeed as a business, especially as he was splitting his time as Square's CEO, and talking about taking a six-month break in Africa. In fact, eight years after going public, Twitter's strongest suit remains that it has lots of users, but its capacity to make money of these users is still questionable. One reason why the market responded so positively, jumping 10% on the news that Dorsey was leaving, is indicative of the relief that change was coming, and the reason that it has fallen back is that it is not clear that Parag Agrawal has what the company needs now. He has time to prove investors wrong, but he is on probation, as investors look to him to reframe Twitter's narrative and start delivering results.

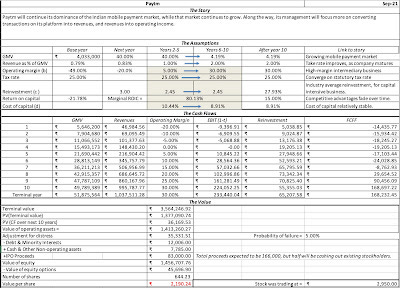

A few weeks ago, I valued one of India's new unicorns, Paytm, an online payment processing company built on the promise of a huge and growing online payment market in India. In my valuation, I told an uplifting story of a company that would not only continue to grow its user base and services, but also that it would increase its take rate (converting users to revenues) and benefit from economies of scale to become profitable over the course of the next decade.

I valued Paytm at about ₹2,200, but in telling that story, I noted one big area of concern with existing management, that seemed to be more intent on adding users and services than on converting them into revenues, and pre-disposed to grandiosity in its statement of purpose and forecasts. In the months since, the company has gone public, and while the offering price, at ₹2150, was close to my value, the stock price collapsed in the days after to less than ₹1400 and has languished at about ₹1600-₹1700 since. It is always dangerous to try to explain why markets do what they do over short periods, but I do think that the company's founders and spokespeople did not do themselves any favors, ahead of the IPO. Specifically, if you were concerned about Vijay Sharma's capacity to convert the promise of Paytm into eventual profits, before the IPO, you would have been even more concerned after listening to him in the days leading into the IPO. It is still too early to conclude that there is a company/CEO mismatch, but if I were top management of the firm, I would talk less about users and gross merchandise value, and focus more on improving the abysmally low take rate at the firm.

If there is a general lessons for investors from this post, it is that when a founder CEO leaves his position, or is pushed out, the value change can be positive or negative, and that good founders will work at making themselves less central to their company's stories over time and thus less critical to its value. It should also be a cautionary note for those investors who have looked the other way as venture capitalists, founders and insiders have fixed the corporate governance game in their favor, in young tech companies that go public, ensuring that mismatches from companies and CEOs, if they occur in the future, will persist.

Family Group Companies: The Life Cycle Effect

In much of the world, businesses, even if they are publicly traded, are run by family groups. To the extent that the top management of these businesses are members of the family, these companies are uniquely exposed to company/CEO mismatches, especially as second or third generations of a family enter the management ranks, and these families enter new businesses.

Family Group Companies: The Life Cycle Effect?

Much of Asian and Latin American business is built around family groups, which have roots that go back decades. Using a combination of connections and capital, these family groups have lived through economic and political changes, and as many of the companies that they own have entered public markets, they have stayed in control. In some cases, this control has come from dominant shareholdings, but more often, it is exercised by using holding company structures and corporate pyramids that effectively leave the family in control, even as the public acquires a larger stake in equity.

To see how the corporate life cycle structure story plays out in family group companies, it is worth remembering that family groups often control companies that spread across many different business, effectively resembling conglomerates in their reach, but structured as individual companies. Consequently, it is not only possible, but likely, that a family group will control companies at different stages in the corporate life cycle, ranging from young, growth companies at one end of the spectrum to declining companies at the other end of the spectrum. In fact, one of the reasons family groups survived and thrived in economies where public markets were under developed was their capacity to use cash generated in their mature and declining businesses to cover capital needs in their growing businesses. This intra-group capital market becomes trickier to balance, as family group companies go public, since you need shareholder assent for these capital transfers. With weak corporate governance, more the rule than the exception at family group companies, it is entirely possible that shareholders in the more mature and cash-generating companies in a family group are being forced to invest in younger, growth companies in that same group.

Implications for CEOs and Management

There is research on CEO turnover in family group companies, and the results are not surprising. In a recent study, researchers looked at 4601 CEOs in companies, classifying them based on whether they were family CEO or outside CEOs, and found the forced turnover was much less frequent in the first group. In other words, family CEOs are less likely to be fired, and more likely to stay around until a successor is found, often within the family. While this is good news in terms of continuity, it is bad news if there is a company/CEO mismatch, since that mismatch will wreak havoc for far longer, before it is fixed.

What can family groups do about dealing with the mismatch, especially as the potential for that mismatch increases, as disruption turns some mature and growing businesses into declining ones and capital gets shifted to new businesses in the green energy and technology space? First, power has to become more diffuse within the family, away from a powerful family leader and more towards a family committee, to allow for the different perspectives needed to become successful in businesses at other stages in the life cycle. If, like me, you are a fan of Succession, the HBO series, you don't want to model yourself on Logan Roy, and the Roy family, if you are a family group company. Second, there has to be a serious reassessment of where different businesses, within the family group, are in the life cycle, with special attention to those that are transitioning from one phase to another. Third, if top management positions are restricted to family members, the challenge for the family will be finding people with the characteristics needed to run businesses across the life cycle spectrum. As many family groups enter the technology space, drawn by its potential growth, the limiting constraint might be finding a visionary, story teller from within the family, and if one does not exist, the question becomes whether the family will be willing to bring someone from outside, and give that person enough freedom to run the young, growth business. Finally, if a mismatch arises between a family member CEO and the business he or she is responsible for running, there has to be a willingness to remove that family member from power, sure to raise family tensions and create fights.

Implications for Investors

Are family group companies, in general, better or worse investments than investments in other publicly traded companies? The evidence, not surprisingly, is mixed, with some finding a positive payoff, which they attribute to a better alignment of long term investor and management interests at these companies, and others finding negative returns, largely as a result of management succession problems.

To address why family control can help in some cases, and hurt in others, it again helps to bring in the corporate life cycle. In the portions of the corporate life cycle, where patience and a steady hand are required, the presence of a family member CEO may increase value, since he or she will be more inclined to think about long term consequences for value, rather than short term profit or pricing effects. On the other hand, if a family CEO is entrenched in a company that is transitioning from growth to mature, or from mature to declining, and is not adaptable enough to modify the way he or she manages the company, it is a negative for value. Family group companies composed primarily of companies in the former grouping will therefore trade at premiums, whereas family group companies that include a disproportionately large number of disrupted or new businesses will be handicapped.

Conclusion

I started this post by talking about Jack Dorsey leaving Twitter, and why the market celebrated that news, but I would like to end on a more general note. If there is a take away from bringing a life cycle perspective to assessing CEO quality, it is that one size cannot fit all, and that a CEO who succeeds at a company at one stage in the life cycle may not have the qualities needed to succeed at another. For boards of directors, in search of new CEOs, my suggestion is that you pay less attention to past track records of nominees, in their prior stints as employees or as CEOs of other companies) and more attention to the qualities that they possess, to see if they match what the company needs to succeed.

YouTube Video