Triggered Disclosures: Escaping the Disclosure Dilemma

In a post a few weeks ago, I argued that the disclosure process had lost its moorings, as corporate disclosures (annual filings, prospectuses for IPOs) have become more bulky, while also become less informative. I argued that some of this disclosure complexity could be attributed to the law of unintended consequences, with good intentions driving bad disclosure rules, and that some of it is deliberate, as companies use disclosures to confuse and confound, rather than to inform. For those of you who agreed with my thesis, the end game looks depressing, as new interest groups push for even more disclosures on their preferred fronts, with the strongest pressure coming from the environmental, social and governance (ESG) contingent. In this post, I propose one way out of the disclosure dilemma, albeit one with little chance of being adopted by the SEC or any other regulatory group, where you can have your cake (more disclosure on relevant items) and eat it too (without drowning in disclosure).

The Disclosure Dilemma: Disease and Diagnosis

For those of you who did not read my first post on disclosures, let me summarize its key points. The first is that company disclosures have become more bulky over time, whether it be in the form on required filings (like annual reports or 10K/10Q filings in the US) or prospectuses for initial public offerings. The second is that these disclosures have become less readable and more difficult to navigate, partly because they are so bulky, and partly because disclosures with big consequences are mingled with disclosure with small or even no consequences, often leaving it up to investors to determine which ones matter. The net effect is that investors feel more confused now, when investing in companies, than ever before, even though the push towards more disclosures has ostensibly been for their benefit.

As we look at the explosion of disclosures around the world, there are many obvious culprits. The first is that technology has made it possible to collect more granular data, and on more dimensions of business, than ever before in history, and to report that data. The second is that interest groups have become much more savvy about lobbying regulatory groups and accounting rule writers to get their required data items on the required list. The third is that companies have learned that converting disclosures into data dumps has the perverse effect of making it less likely that they will held accountable, rather than more. That said, there are three other reasons for the disclosure bloat:

The first is the prevailing orthodoxy in disclosure is tilted towards "one size fits all", where all companies are covered by disclosure requirements, even if they are only tangentially exposed. Though that practice is defended as fair and even handed, it is adding to the bloat, since disclosures that are useful for assessing some firms will be required even for firms where they have little informative value.

The second is the notion of materiality, a key component of how accountants and regulators think about what needs to be disclosed. Using the words of IFRS (1.7), ‘Information is material if omitting, misstating or obscuring it could reasonably be expected to influence decisions that the primary users of general purpose financial statements make on the basis of those financial statements, which provide financial information about a specific reporting entity’. As we will argue in the next section, this definition of materiality may be leading to too much disclosure for backward looking items and too little for forward looking items.

The third is that the disclosure rule writers happen to be in the disclosure business, and since more disclosure is good for business, the conflict of interest will always tilt toward more rather than less disclosure. No matter how many complaints you hear from accountants and data services about disclosure bloat, it has been undeniable that it has created more work for accountants, appraisers and others in the disclosure ecosystem.

It is quite clear, though, that unless we break this cycle, where each corporate shortcoming or market upheaval is followed by a fresh round of new disclosures, we are destined to make this disclosure problem worse. In fact, there may come a point where only computers can read disclosures, because they are so voluminous and complicated, perhaps opening the door for artificial intelligence or matching learning into investing, but for all the wrong reasons.

Escaping the Disclosure Trap

There is a way out of this disclosure trap, but it will require a rethink of the status quo in disclosures. It starts first by moving away from "one size fits all" disclosure rules to disclosures tailored to companies, a "triggered" disclosure process, where a company's value story (big market, lots of subscribers) triggers disclosures on the parameters of that story. It extends into materiality, by reframing that concept in terms of value, rather than profits, and connecting it to disclosure, with disclosure requirements increasing proportionately with the value effect. Finally, it requires creating a separation between those who write the disclosure rules and those who make money from the disclosure business.

One size (does not) fit all!

When disclosure laws were first written in the aftermath of the great depression, they were focused on the publicly traded firms of the time, a mix of utilities, manufacturing and retail firms. At the time, the view that disclosure requirements should be general, and apply to all companies, was rooted in the idea of fairness. In the decades since, there have been exceptions to this general rule, but they have been narrowly carved out for segments of firms. For instance, oil companies are required to disclose their ownership of "proven undeveloped reserves", in addition to details about quantity, new investments and progress made during the year in converting those reserves. The disclosure rules for banks and insurance companies require them to reveal the credit standing of their loan portfolios and their regulatory capital levels to investors and the public. These exceptions notwithstanding, disclosure laws written to cover concerns in one sector (such as the use of management options at technology firm or lease commitments at retail and restaurant companies) have been applied broadly to all companies. It is time to rethink this principle and allow for a more variegated disclosure policy, with some disclosures required only fir subsets of companies. Since the next big bout of disclosures that are coming down the pike will be related to ESG, this discussion will play out in a wide range of ESG data items. For instance, while it makes sense to require that fossil fuel and airline companies report on their carbon footprints and greenhouse gas emissions, it may just be a time consuming and wasteful exercise to require it of technology companies.

From earnings-based to value-based materiality

I do not think that you will find many who disagree with the premise that any information that has a material effect should be disclosed, but there is disagreement on what comprises materiality. I believe that the "materiality principle", as defined by accountants, is diluted by measuring it in terms of impact on net income and the fact that accountants tend to be naturally conservative in measuring that impact. Simply put, it is safer for an accounting or audit firm to assume that a disclosure is material, and include it in reports, even if it turns out to be immaterial, than it is to assume that it is immaterial, and be found wrong subsequently. One solution to this problem is to redefine materiality in terms of effects on value, rather than earnings, thus accomplishing two objectives. First, it will reduce the number of noise disclosures, i.e., those that pass the materiality threshold for earnings, but don't have a significant impact on value. Second, since value is driven by expected cash flows in the future and not in the past, it will shift the focus on disclosures to items that will have an impact on future earnings and cash flows, rather than on past earnings or book value.

Triggered Disclosures

At first sight, the requirements to make disclosures slimmer and more informative may seem at war with each other, since disclosure bloat has largely come from well-intentioned attempts to make companies reveal more about themselves. Triggered disclosures, where disclosures are tailored to a company's make-up and stories, are one solution, where contentions made by a company trigger additional disclosures related to that contention. Thus, a company that claims that brand name is its supreme competitive advantage would then have to provide information to not only back up that claim, but also to allow others to value that brand name.

Disclosure Illustration: Initial Public Offerings

It is difficult to grapple with disclosure questions in the abstract, and to illustrate how my proposed solutions will play out in practice, I will focus on initial public offerings, where there is a sense that the disclosure rules are not having their desired effect. In my last post, I noted that prospectuses, the primary disclosure documents for a companies going public, have bulked up, contrasting the Microsoft and Apple prospectuses that came in at less than a 100 pages in the 1980s to the 400+ page prospectuses that we have seen with Airbnb and Doordash in more recent years. At the same time, applying a disclosure template largely designed for mature public companies to young companies, often with big losses and unformed business models, has resulted in prospectuses that are focused in large parts on details that are of little consequence to value, while ignoring the details that matter. Since companies going public often do so on the basis of stories that they tell about their futures, and these stories vary widely across companies, this segment lends itself well to the triggered disclosure approach. To do so, I will draw on a paper that I co-wrote with Dan McCarthy and Maxime Cohen, to provide details. In that paper, we argue that a going-public company that wants to build its story around certain dimensions (a large total addressable market or a large user base) will trigger disclosure of a more systematic, business type-specific, collection of “base disclosures” that are required to understand the economics of businesses of that type, whatever type that might be.

Total Addressable Market (TAM)

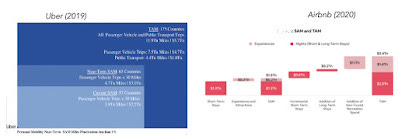

Companies going public have increasingly supported high valuations by pointing to market potential, using large TAMs as one of the justifications. These TAMs are often not only aspirational, but also come with very little justification and no timeline for how long it will take for the existing market sizes to grow into those TAMs. For instance, the graph below shows the TAMs that Uber and Airbnb claimed in their prospectuses at the time of their initial public offerings.

Uber and Airbnb ProspectusesIs Uber’s total addressable market really $5.2 trillion? I don’t think so, but you can see why the company was tempted to go with that inflated number to push a “big market” narrative. To prevent the misuse of TAM as little more than a marketing ploy, companies that specify a TAM should also have to provide the following:

a. TAM, SAM and bridges: Companies that specify a TAM should also specify the existing market size (i.e., the serviceable addressable market or SAM), as well as additional “bridges” so that investors can understand the evolution from SAM to TAM (e.g., an estimate of how many individuals would be interested in the company’s product before considering price). Investors who may be skeptical of a lofty TAM could still look to SAM as a more achievable intermediate metric.

b. Market share estimates: As long as companies do not have to twin TAM with expectations of market share, there is little incentive for them to restrain themselves when estimating TAM. We would recommend requiring that companies that disclose TAM figures couple them with forecasts of their market share of those TAM figures. For companies that are tempted to significantly inflate their TAMs, the worry that they will be held accountable if their revenues do not measure up to their promises, will act as a check.

c. Ongoing metrics or measures: Companies usually provide TAM, SAM, and variants thereof on a one-shot basis, disclosing these figures in their pre-IPO prospectuses and then never again. We believe that investors should be given these measures on an ongoing basis. This will help on two levels. First, it will allow investors to see how well the company is adhering to its prior disclosures and forecasts and provide investors with updates if conditions have changed. Second, companies that know they will be held accountable to their IPO disclosures after they go public will be more incentivized to make those disclosures realistic and achievable.

To the extent that investors will continue to assess premiums for companies that have bigger markets, the bias on the part of companies will still be to overestimate TAM. That said, these recommendations should help rein in some of those biases.

Subscription-Based Companies

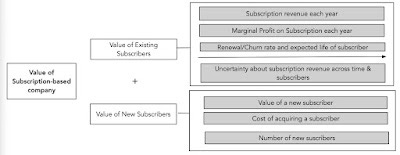

A subscription-based company derives its value from a combination of its subscriber base (and additions to it) and the subscription fees its charges these subscribers. Consequently, the value of an existing subscriber can be written as the present value of the expected marginal profit (subscription fee net of the costs of servicing that subscription) from the subscription each year, over the expected life of the subscriber (based upon renewal/churn rates in subscribers), and the value of a new subscriber will be driven all of the same factors, net of the cost of acquiring that subscriber. The overall value of the company can be written in terms of its existing and new subscribers:

Companies that sell a “subscriber” story have the obligation, then, to provide the information needed to derive this value:

Existing subscriber count: Observing the total number of subscribers in each period (e.g., month or quarter) allows us to track overall growth trends in the number of subscribers, and to understand how revenue per subscriber evolves over time, because revenue is disclosed.

Subscriber churn: To value a subscriber, a key input is the renewal rate or its converse, the churn rate. Holding all else constant, a subscription business with a higher renewal rate should have more valuable subscribers than one with a lower renewal rate. It would stand to reason that any subscription-based company should report this number, but it is striking just how many do not disclose these measures or disclose them opaquely. For example, while the telecom industry regularly discloses churn figures, Netflix has not disclosed its churn rate in recent years.

Contribution profitability: For subscribers to be valuable, they need to generate incremental profits, and to estimate these profits, you need to know not just the subscription fees that they pay, but also the cost of servicing a subscription; the net figure (subscription fee minus cost of service) is called the contribution margin. Many subscription companies explicitly disclose contribution profits (e.g., Blue Apron, HelloFresh, and Rent the Runway), but many others do not (e.g., StitchFix). In the absence of explicit contribution profit data, investors often resort to simple proxies for it, such as gross profit, but these proxies are imperfect and noisy.

Subscriber acquisitions & drop offs: To move from the value of a single subscriber to the value of the entire subscriber base, we must also know how many subscribers are acquired over time, not just the net subscriber count. Put differently, if a company grew the overall size of its subscriber base from 10 million to 12 million subscribers in a year, it is quite different if that net growth came about because the company acquired 10 million customers that year but then lost 8 million of them, versus if the company acquired 2 million customers and lost none of them. Acquisition (or equivalently, churn) disclosures are what allow us to piece this apart.

Cost of acquiring subscribers (CAC): Subscription-based companies attract new subscribers by offering special deals or discounts, or through paid advertising. While the cost of acquiring subscribers can sometimes be backed out of other disclosures at subscription-based companies (such as subscribers numbers, churn and marketing costs), it would make sense to require that it be explicitly estimated and reported by the company.

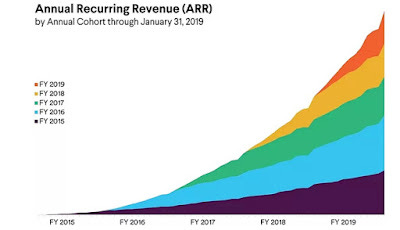

Cohort data: While many subscriber companies are quick to report total numbers, only a provide a breakdown of subscribers, based upon subscription age. This breakdown, called a cohort table, can be informative to observe retention and/or monetization patterns across cohorts, as noted by Fader and McCarthy in their 2020 paper on the topic. Many subscription-based firms, including Slack, Dropbox, and Atlassian, now disclose cohort data, and the figure below shows one such chart for Slack Technologies:

Source: Slack Technologies Form S1

By breaking down cohort-specific retention and monetization trends, a cohort chart offers investors visibility into retention and development patterns as a function of subscriber tenure (e.g., does the retention rate get better or worse as subscribers get older), and trends across time, as subscribers stay on the platform.

Transaction-Based Companies

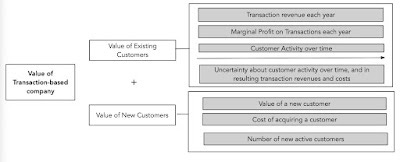

The guiding principles driving our disclosure recommendations for subscription-based businesses largely extend to transaction-based businesses, with the primary difference being that subscription revenues are replaced with transaction revenues, a number that is not only more difficult to estimate, but one that can vary more widely across customers. The value of the customer base at transaction-based businesses is driven off the activity of these customers, translating into transaction revenues and profits.

As with subscriber-based businesses, this framework can only be used if the company provides sufficient data from which one can estimate the inputs. Deconstructing this picture, many of the key disclosures track those listed for subscription based companies, including contribution profitability, customer acquisition costs and cohort data. In addition, there are three key additional pieces of information that can be useful in valuing these companies:

Active customer count: We replace the notion of a subscriber with that of an “active” customer, which is more suitable for transaction-based businesses. After all, a customer in your platform who never transacts is not affecting value, and one issue that transaction-based companies have struggled with is defining "activity". Wayfair, Amazon, and Airbnb, for example, define an active customer to be one who has placed at least one order over the past 12 months. In contrast, Lyft, Overstock, and many other companies define a customer as active if they placed an order in the past 3 months.

Total orders: In transaction-based companies, the average purchase frequency of active customers can change, often significantly, over time. We need to know the total orders because this further allows us to decompose changes in revenue per active customer into changes in order frequency per active customer and changes in average order value. While some transaction-based businesses disclose this information, including Wayfair, Overstock, Airbnb, and Lyft, this data is notably absent for many others, such as Amazon.

Promotional activity: It can be easy to significantly increase purchase activity through enticing targeted promotions, creating the illusion of rapid growth that may not be sustainable over the long run, due to their substantial cost. Since these promotions are often reported as revenue reductions, rather than expenses, the cost of these campaigns are often opaque, to investors. For example, DoorDash did not disclose their total promotional expense during the most recent 6 months in their IPO prospectus, creating substantial uncertainty for investors as to how this may have influenced gross food sales).

Fintech Companies

In the last decade, we have seen banks, insurance companies and investment firms face disruption from firms in the "fin-tech" space, covering a diverse array of companies in the space. With all of these companies, though, there is (or should be) a lingering concern that part of their value proposition comes from "regulatory arbitrage", i.e., that these disruptions can operate as financial service companies, without the regulatory overlay that constrains these companies, at least in their nascent years. Since this regulatory arbitrage is a mirage, that will be exposed and closed as these fin-tech companies scale up, investors in these companies need more information on:

Quality/Risk metrics on operating activity: In the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, banks, insurance companies and investment banks have all seen their disclosure requirements increase, but ironically, the young, technology-based companies that have entered this space seem to have escaped this scrutiny. In fact, the absence of a regulatory overlay at these companies makes this oversight even more dangerous, since an online lender that uses a growing loan base as its basis for a higher valuation, but does not report on the default risk in that loan base, is a problem waiting to blow up. It is highly informative for investors to observe the evolution of these measures in the years and quarters leading up to the IPO. Indeed, lenders can be tempted to strategically lower their credit standards to issue more loans (and hence significantly increase revenue through loan-related fees, which are often assessed upfront) to create the illusion of growth at the expense of long-term profitability and trust (since many of these risky loans are likely to default in the future).

Capital Buffer: It is worth remembering that banks existed prior to the Basel accords, and that the more prudent and long-standing ones learned early on that they needed to set aside a capital buffer to cover unexpected loan losses or other financial shortfalls. In the last century, regulators have replaced these voluntary capital set asides, at banks and insurance companies, with regulatory capital needs, tied (sometimes imperfectly) to the risk in their business portfolios. Many fintech companies have been able to avoid that regulatory burden, largely because they are too small for regulatory concern, but since they are not immune from shocks, they too should be building capital buffers and reporting on the magnitude of these buffers to investors.

Conclusion

As data becomes easier to collect and access, the demands for data disclosure from different interest groups will only increase over time, as investors, regulators, environmentalists and others continue to add to the list of items that they want disclosed. That will make already bulky disclosures even bulkier, and in our view, less informative. There are three ways to have your cake and eat it too. The first is to allow for increasing customization of disclosure requirements to the firms in question, since requiring all firms to report everything not only results in disclosures becoming data dumps, but also in the obscuring of the disclosures that truly matter. The second is to shift the materiality definition from impact on earnings to impact on value, thus moving the focus from the past to the future. Finally, tying disclosures to a company's characteristics and value stories will limit those stories and create more accountability.

YouTube Video

Papers

Initial Public Offerings: Dealing with the Disclosure Dilemma (with Dan McCarthy and Maxime Cohen)

Blog Posts